“A migrant is someone who moves from one place to another, often with the hope of finding a better opportunity or better living conditions.”

For thousands of years people have travelled across various lands, relocating from one place to another, building and rebuilding their homes and lives. Historically, the need to relocate first occurred due to changes in climate and shortages of food. Today people migrate both within their own country and abroad, for a new job, university, to live with family, for greater opportunities, due to political situations or simply because they want to travel. For the majority of readers the act of relocating home to gain access to food supplies would not be necessary. Though across our seas, relocating for food, shelter and basic health care remains an on-going battle.

In 2015 the word ‘migrant’ was written again and again across newspaper articles, declaring Europe’s ‘migration crisis’. Images of people crammed into small boats and dinghy’s in the hope of migrating, desperately swimming in the sea and washed up cold on the shore stood amongst the vast array of press images that were being published on a daily basis. Photographer, Daniel Castro Garcia noticed these floods of images and felt concerned at the ways in which the British press was responding to the crisis:

“The moment that made me book my ticket to go and see this situation for myself was in April 2015 when two vessels capsized within the space of one week where an estimated 1,000 people drowned. The response from the British press was pitiful to say the least and many columns were written with truly alarming tones and shocking vocabulary. My belief was that within these big, dramatic crowd shots were individuals, each with their own reasons for coming to Europe and they deserved to be heard and listened to.”

Lampedusa, Sicily, Italy, January 2017

The hull of a migrant/refugee boat which now rests in a large boat graveyard in a secluded area of the island. Over one hundred people are often packed into the hull of these boats at great risk to themselves. These are the “cheap seats” and passengers face multiple risks such as hypothermia, asphyxiation from engine fumes and chemical burns from petrol mixing with seawater.

Castro Garcia travelled and worked with friend and designer Thomas Saxby, who like himself has a parent who migrated to Britain. Travelling across the world to see the impact of the migration crisis on refugees and to be among deprivation and conflict is not a journey that many people would feel emotionally able to experience. Castro Garcia notes that when asked about the psychological impact of his experiences, he would often think, “I wanted to do this and see it… I have a responsibility to be strong and unemotional.” Though as time passed and Castro Garcia established relationships with those he met, it became harder for him to maintain the emotional resilience he first had, “As time has gone on and this project has grown,[AF1] it has affected me… I have witnessed things I never thought I would see; people being treated like animals and currency, people living surrounded by faeces, rats and[AF2] hunger. I have attended memorials for people that were killed in hit and runs on the motorway by the Calais “Jungle” where no one was held to account. I was present when the body of a Sudanese man named Gouma Makhil was found in a shelter; he had died due to the cold at night. It has been very difficult to be a part of the European society that has let this happen.”

Despite these unimaginably difficult experiences, meeting some of the refugees of the migration crisis enabled Castro Garcia to form meaningful relationships and friendships that came to shape his life. One such friendship was with Aly Gadiaga, who left his family and home in Senegal and spent three years travelling to Libya, where he washed dishes in Mali and Burkina Faso. The money Gadiaga earned allowed him to cross the Sahara desert in a pick-up truck convoy. He currently lives in Catania, where he has been based for the past five years; he has only recently been able to secure a work permit. Castro Garcia met Gadiaga in a market in Catania and has remained in touch with him every day[AF3] since.

Here Castro Garcia shares Gadiaga’s own words;

“Explaining the reason for migration is easy. Take a room. Put a cat inside it. For two days you don’t give it food or water. The room is locked. If you forgot to close the window and after two days the cat has seen it’s open… what does the cat do? He escapes! He climbs through the window and escapes from the hunger. The cat knows that if it stays there it will die of hunger in the room. If he can see the window is his only chance of freedom, what will he do? One can’t be without food… without water…

I think we are all the same, each of us hope to have a beautiful future. A person shouldn’t have to wait for four or five years without documents without knowing if he will ever get them. This time is very important. The time that you have lost you will never have again. So why should they make people waste five years? Just one day… 24 hours is so important in someone’s life. In just 24 hours you can do so many important things, not just for yourself, but for the whole world. For me this is a chance for Europeans to realise that Europe is the most democratic continent in the world. They respect human rights. They exercise liberty for all. Equality. We should all be equal.”

This group of men arrived on the island of Lampedusa one week prior to this image being taken. They had experienced a particularly rough journey and all expressed their trauma of what was faced at sea. They had little information regarding their situation in Lampedusa and did not know when they would be transferred to mainland Italy.

The photograph of Gadiaga, taken in November 2015 depicts him stood side on, in profile, on a beach. Though his eyes are downcast, as if slightly removed in thought, his physical presence fills the left side of the photographic frame. With his right arm outstretched it can be easy to miss the wisps of sand that gently glide from his clenched fist. Soft blue skies appear to be nearing the start of sunset and golden rays of light tickle Gadiaga’s skin. There appears to be no one else around though the sand is covered in the footsteps of others, hinting at their past arrival and departure. Gadiaga stands as both a visitor to the beach and as an individual in the midst of his own journey. Like the sand that drifts in the direction of the wind, Gadiaga is also in flight.

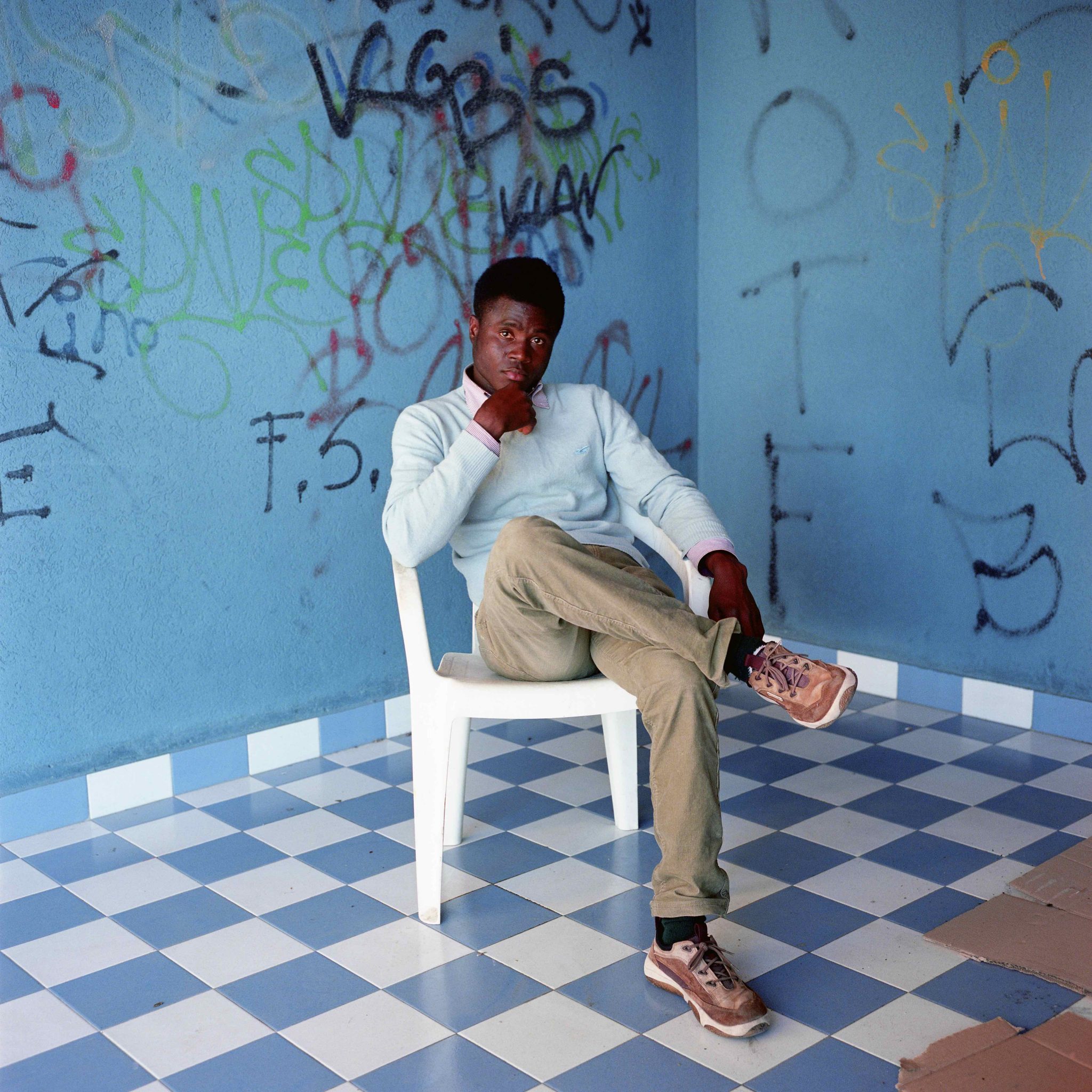

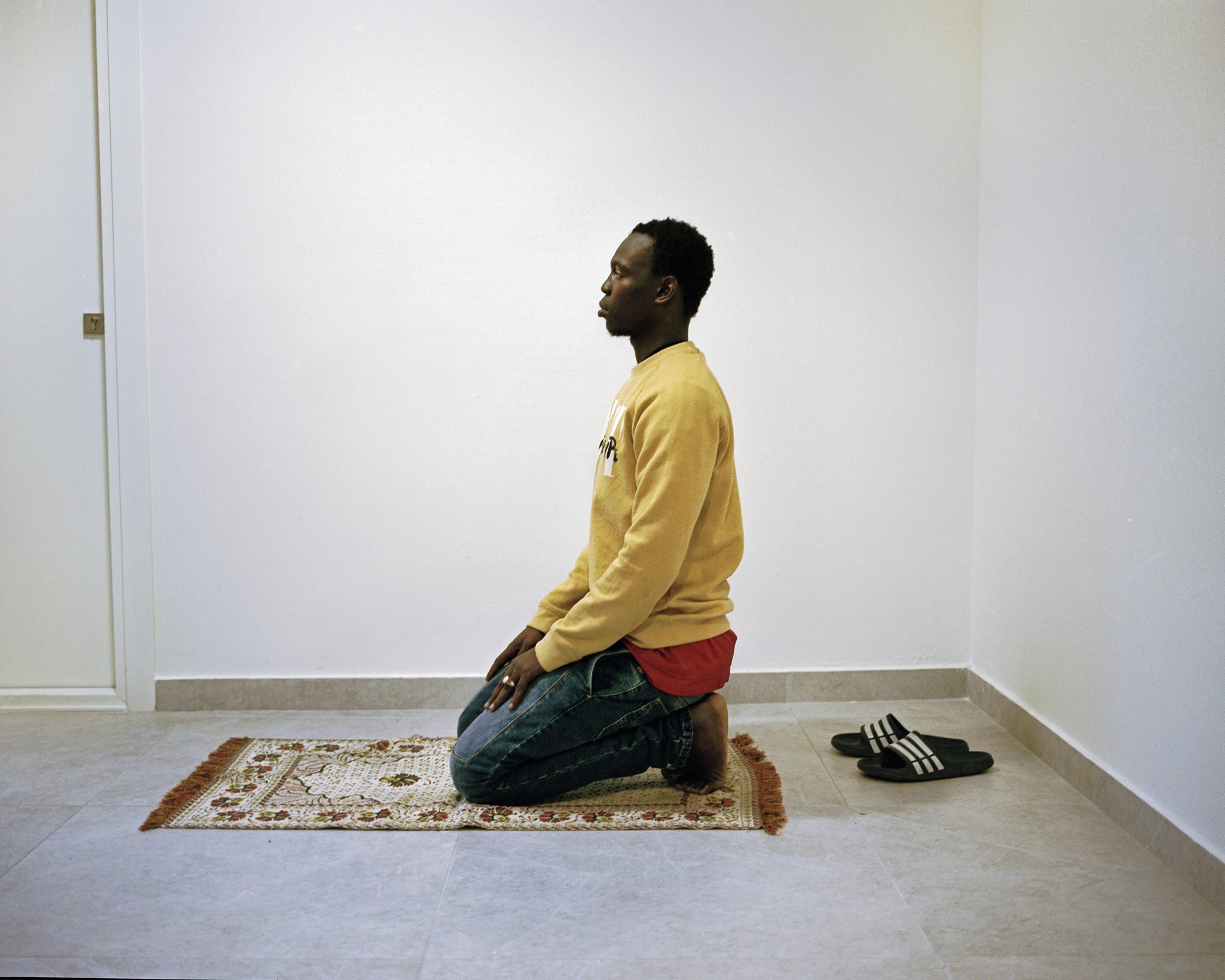

Catania, Sicily, Italy, January 2017

Portrait of Aly Gadiaga praying taken during the filming of “Gucci… The Journey of Aly.”

When moving to various borders and campsites Castro Garcia disclosed that his position often altered from being a witness to other people’s lives, to a companion, listening to the stories and sharing in the daily experiences of others. It has been this willingness to connect to others that in turn enabled them to be so open to being photographed. In 2015 Castro Garcia met and photographed a group of Sudanese men playing cards to pass the time in Calais. The men in this image are gathered around a table and largely have their focus toward the card game. In the centre of the image, one man is captured looking directly toward Castro Garcia’s lens. With his hand placed underneath his chin he softly smiles. The invitation toward Castro Garcia allowed him to capture a moment of friendship and tranquillity that could easily have been missed amongst the chaos of these individual’s lives.

Similarly in 2017 Castro Garcia photographed a group of men who had not long arrived on the island of Lampedusa. When travelling across the sea, these men had faced high risks of hypothermia, asphyxiation from engine fumes and chemical burns from petrol mixing with seawater. On the island they had no information as to when they would be transferred to Italy; the strains of their journey can be seen across their faces. Though less tranquil than playing a game of cards, the men in this photograph still want to be photographed and noticed. They are willing to share their stories and allow Castro Garcia to join them in a segment of their journey.

Lampedusa, Sicily, Italy, January 2017

Mr. Happy, from Nigeria, spoke of his delight to have been so warmly received by the Christian community in Lampedusa. At the church in the main square, volunteers hand out clothing and rosaries for anyone that wants one.

In being empathetic to the suffering and situations of those he meets, Castro Garcia is able to capture day-to-day moments of refugee’s lives that often become lost within the chaos of press images. He enables his viewers to look again. Castro Garcia comments:

“Where so much of the imagery in this subject is gritty and sensational, I am more interested in working with someone to find out what they want to express about themselves, what do they want to show and communicate to the rest of the world?…I want to integrate in the community I am working with and stay together. Work together. Think together. I have no interest in turning up somewhere, snapping a few pictures and disappearing. I’m not criticising anyone that does that, it’s simply not for me.”

To take a chance and get on a boat without any real knowledge that you will make it safely across the sea, to be without food and care, and to depart from your family requires huge levels of both desperation and resilience. At times, continuous struggles can lead our determination and self-belief to fade. It is in these moments that we need to be able to rely on the support of others. In January 2017, Castro Garcia met ‘Mr. Happy’, from Nigeria, who spoke to him about the Christian community in Lampedusa who welcomed and accepted him, offering him and other migrants clothing and rosaries. It was with this support that he continued to stay positive about his future. On his travels, Castro Garcia also remarks on having seen some remarkable work by the charity Help Refugees UK and its volunteers. In the face of continuous uncertainty, many migrants are also joining and working together. This collective resilience is paramount for helping those in need reach the futures they deserve.

Words: Emma Bourne

Artist: Daniel Castro Garcia