“I have wanted to visit Graceland for years, and I’ve had a long-time fascination with the way some public figures become an icon or a symbol rather than a real person after their death.” With this idea in mind, London-based photographer, Hayley Louisa Brown visited Memphis twice over the past two years to explore Elvis Presley’s vast legacy. Characterised by authentic realism and a strong desire for documentation, Children of Graceland is Brown’s latest photographic project, which was showcased from 17 – 19 November at Protein Studios in East London.

“I have wanted to visit Graceland for years, and I’ve had a long-time fascination with the way some public figures become an icon or a symbol rather than a real person after their death.” With this idea in mind, London-based photographer, Hayley Louisa Brown visited Memphis twice over the past two years to explore Elvis Presley’s vast legacy. Characterised by authentic realism and a strong desire for documentation, Children of Graceland is Brown’s latest photographic project, which was showcased from 17 – 19 November at Protein Studios in East London.

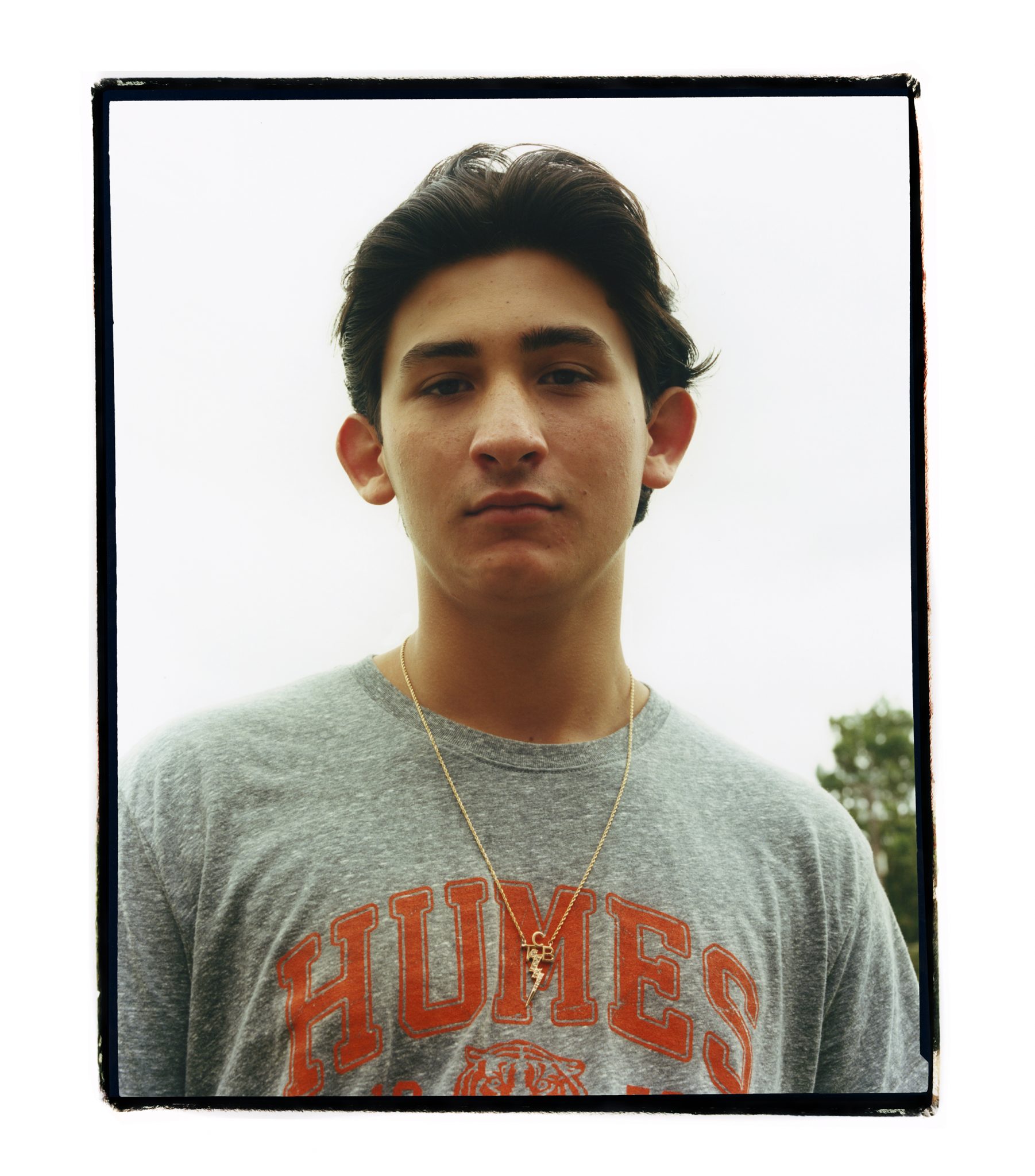

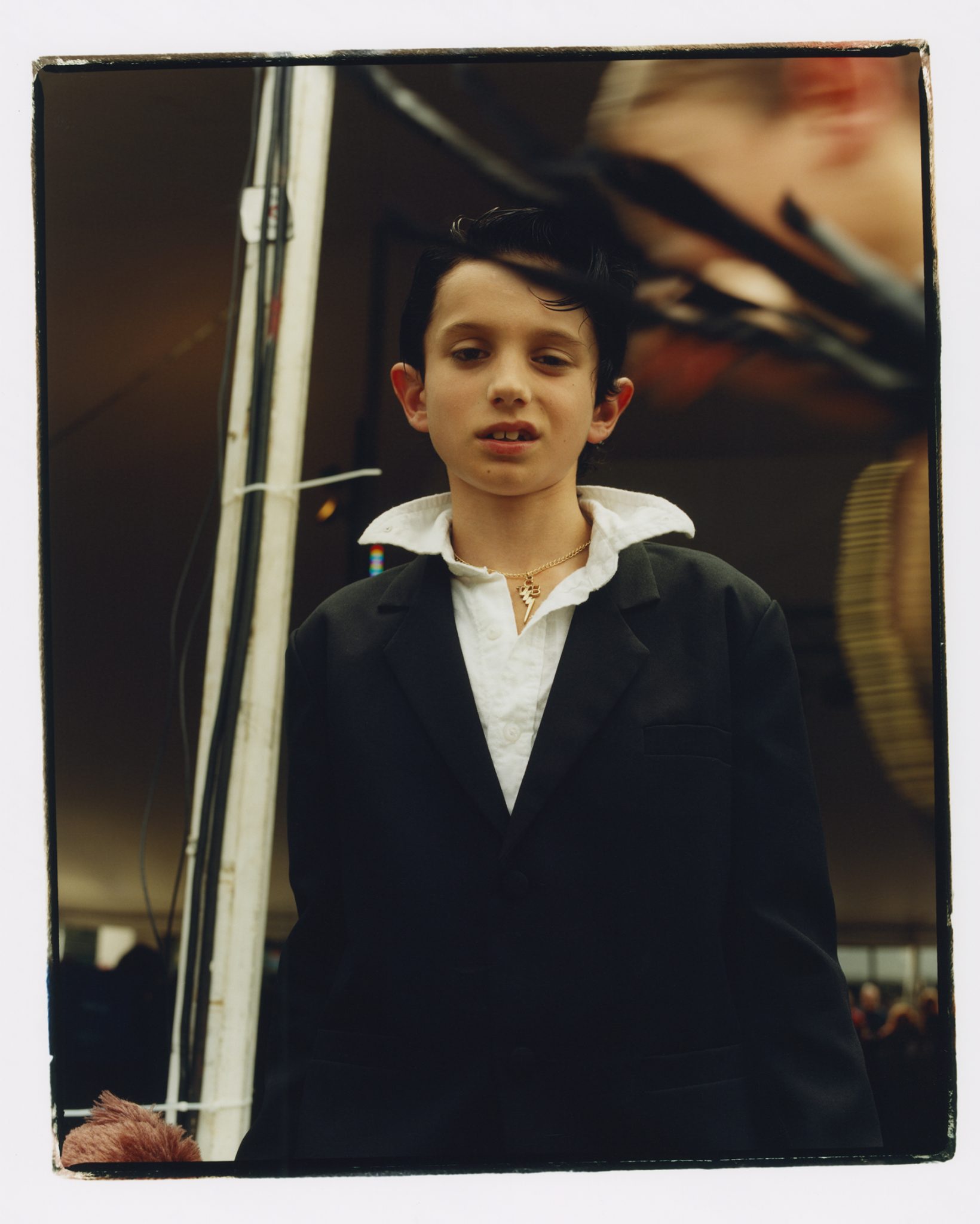

This new set of photographs displays contemporary symbols of Graceland and beautiful portraits of young Elvis fans, reinforcing the idea that the ‘The King of Rock and Roll’ is indeed a long-lasting icon. The portraits of Children of Graceland feature the people who work at Graceland; for the most part, they are Black African American teenagers, who are employed part-time and have no interest in Elvis’ life and legacy. Rather than offering a romanticised idea of Memphis and presenting Elvis as a legend, Brown develops a more realistic and politicised view on Elvis as a man and Graceland as an actual place with real people and stories.

Children of Graceland, a new exhibition at Protein Studios supported by Ace & Tate Creative Fund, sees your journey to Elvis Presley’s estate and explores its significance these days. Where did your idea for the project come from?

I have wanted to visit Graceland for years, and I’ve had a long-time fascination with the way some public figures become an icon or a symbol rather than a real person after their death. People like Marilyn Monroe, James Dean, and Elvis. The idea of photographing young fans came from my curiosity regarding the longevity of Elvis’s legacy, and who was replenishing a fan-base that was, as morbid as it sounds, dying out. The artist Peter Blake was interviewed about his work featuring images of Elvis Presley and he said he was interested in the legend of Elvis, rather than the man himself, which is how I feel, too.

What sort of impact did Graceland have on you? Was it what you thought it would be?

It wasn’t at all what I imagined it to be. I had really romanticised the idea of the place. Last year I visited his honeymoon home in Palm Springs, and the tour was just myself and my boyfriend with the couple who host them. We were allowed to sit on the bed, look in the wardrobes, everything. It was the polar opposite of the rigorous enterprise at Graceland which made actually heading to Graceland even more of an alien experience. Everything from the location to the staff was unexpected, and I’m glad I was able to be there both before and after it was renovated to see how everything was affected by this shiny and new exterior.

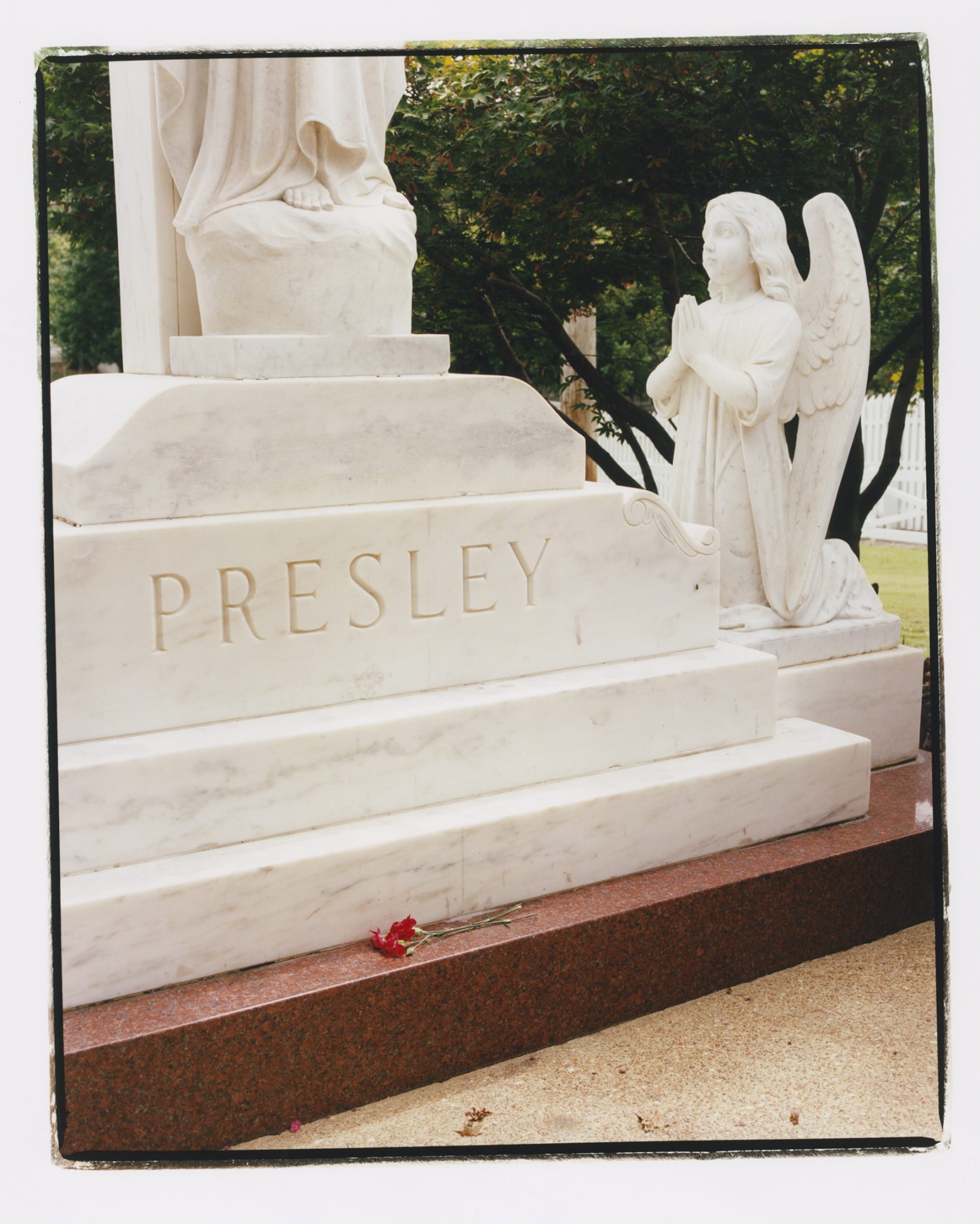

The exhibition presents a striking series of portraits alongside Graceland’s signs, photographs and even Elvis’ tombstone. Considering that the media have completely neglected the last ten years of his life and portrayed him as an attractive young man, do your photographs intend to illuminate such contrast between Elvis-reality and Elvis-legend? Could you tell us a bit more about this disparity?

I wanted to show the lack of attention paid to Elvis’s downfall through the incidental images of Graceland, for example, one of a floral display from beside his tomb that reads ‘forever young and beautiful’. The merchandise at Graceland is also conspicuously absent of any signs of his aging, too, so photographing the young fans wearing their shirts with his equally young face on was also a subtle way to touch on that.

Your portraits convey your interest in the relationship between Elvis’ music and the people of Memphis, in particular how his legacy lives on for Graceland’s youngest visitors. In some of your photos, you even captured children who impersonate Elvis. What did you discover about the people you met in Memphis?

There are so many stories I can barely make a dent on them in answering this question! I was in the city for quite a long time, with most of my days spent at Graceland, so I used up many hours chatting away to the young staff who work there, especially on the slow days. I found out that for many of them, unsurprisingly, it was just a part-time job. It wasn’t something they did because they love Elvis. In contrast, you had people who had flown from Australia just to visit Graceland and who were beyond thrilled to be there. Memphis is a city like any other, with political undercurrents and so many other narratives running through it – it just happens to be the place that Elvis lived.

A lot of your work is influenced by hip-hop culture. In fact, you have founded BRICK, a magazine entirely dedicated to this music genre. Do you think this exhibition is somehow connected with your practice more generally?

All of my work centres around subculture and music, so it’s absolutely connected in that sense. I always try to capture something honest, regardless of who or what is in front of the camera, so I don’t feel like my work has to be separated into categories.

Children of Graceland is your first exhibition. What was the experience like?

So much fun! I had a really great team of people working with me to bring my vision for the show to life, both from Ace & Tate and Protein, and it all still seems a little surreal.

Do you have other exhibitions planned for the future?

I’d definitely like to do some more shows. I was lucky enough to be supported by Ace & Tate’s creative fund for Children of Graceland, which gave me enough support that I could really throw myself into the project. We’ve just sent the next issue of BRICK off to the printers so that will be the next thing!

Words: Fiorella Lanni

Editor: Emma Bourne