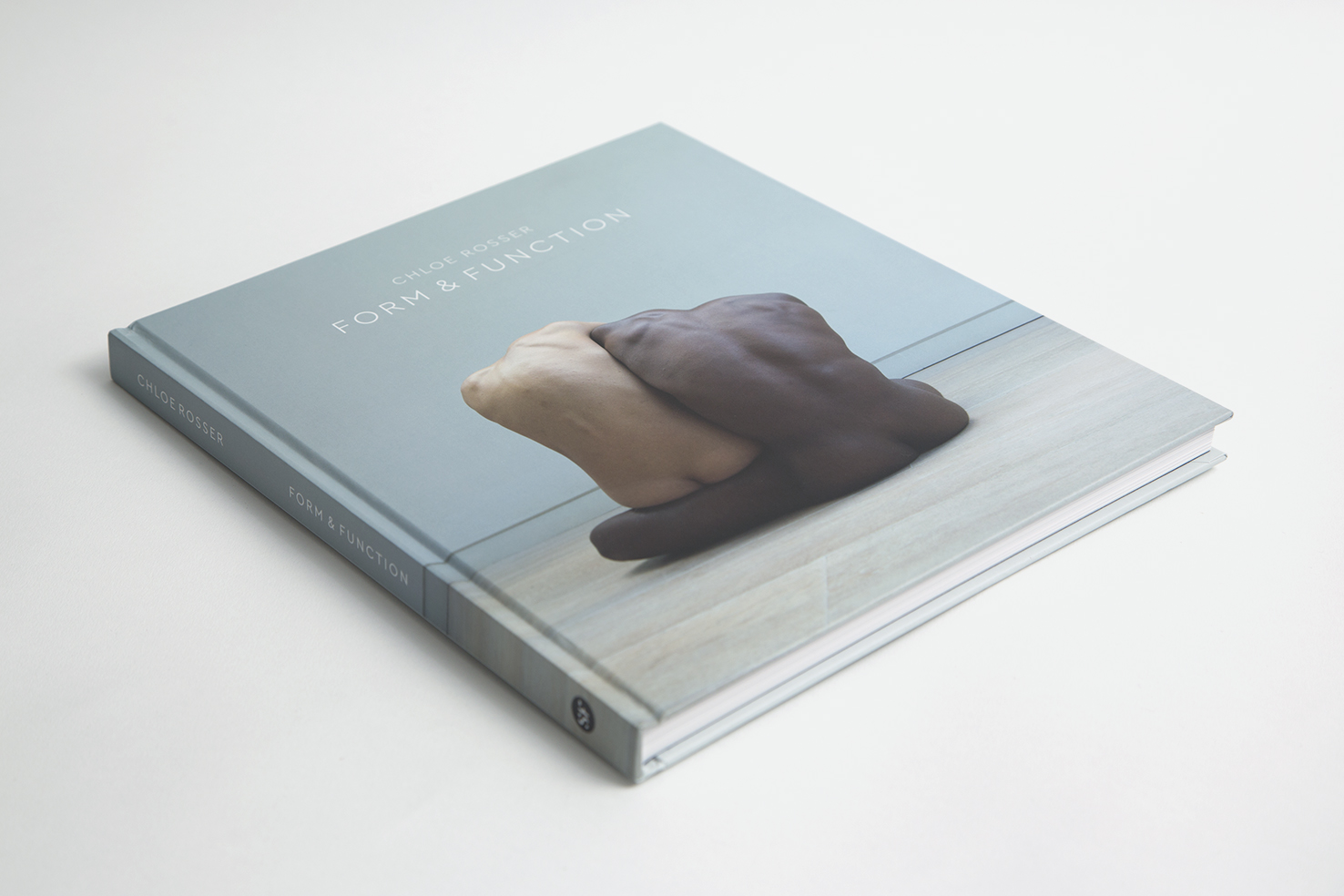

Photography: Chloe Rosser

Interview: Fiorella Lanni

‘Photography is the only medium which allows me to sculpt with human flesh. The human body is the most intimately familiar thing to us. Seeing it in these strange poses affects you deeper than if you were to see a similar sculpture because it’s real, and you can imagine being it and feeling what it feels’. With this idea in mind, London-based photographer, Chloe Rosser, conceived Form and Function– an ambitious collection of photographs taken over the last five years. Challenging the human condition and our relationship with bodies, Rosser’s photographs alter our mainstream perceptions of human bodies by creating shapes that embrace contemporary concepts of gender fluidity and inclusivity.

Form and Function promotes body positivity, displaying scars, wrinkles, and other imperfections. Rosser’s photographs feature models of all shapes, races, and age. It is often indistinguishable whether the subject is a man or a woman. Their bodies twist, bend, and stretch, before they eventually blend together into intimate, and sometimes grotesque sculptures.

Form and Function was displayed with L A Noble Gallery at Photofusion last year. The book is published with Stay Free Publishing and was funded through Rosser’s Kickstarter campaign.

Highly debated and wrapped in controversy, our relationship with the human body is arguably now more complicated and widely discussed than ever before. What was your first inspiration behind the project? And why did you choose the title Form and Function?

Before Form and Function, I had been working with the human body for a little while, but what I was doing wasn’t really working. I was cropping them in certain ways, none of which were very strong. I wanted to abstract it and create shapes out of it. And then I took a photo of the back of someone’s torso, they were sat down and bent forward, you couldn’t see anything apart from this cube of flesh and it was so strange and different from what I had been doing that I really felt like that was something I needed to explore more. One of the reasons why that image was so powerful and arresting to me was that I was looking at a lump of flesh which appeared both beautiful and grotesque at the same time. Most people look at these images and think they are Photoshopped, when in fact these surreal bodies are very much real.

I then started coming up with a great variety of poses, I would take the body and try to make it almost as inhuman as possible. That’s how Form, the first part of the project, came about. I developed Function out of a desire to establish an interaction and connection between the bodies, and to question our assumption of what it means to live in a body. We often act as if the function of the human body is to look attractive. These days there is such a strong focus on looking good and physical appearance, when the real function of the body is to breathe, live. My project wants to be a reminder of that.

A lot of the poses, especially in Form, are quite foetal, with a certain vulnerability to them. They are often curled in a fragile way that’s also got a strange and repulsive side to it. When I moved to Function, I started photographing two or more people. I was really trying to explore the relationship between the bodies and how that visually played out. A lot of them are leaning on each other and supporting one another. They have to reach a point of equilibrium with the other person to be able to hold that perfect balancing pose.

By looking at your photographs, one can really feel your engagement with the subjects. Could you tell us a bit more about the creative process behind each photograph and how you select your subjects?

There is a whole variety of people in my photographs, some are life models, some are my friends, and others are people who got in contact because they wanted to be part of the project. All the experiences I have had so far have been very good, and all very different depending on who I am photographing. Some people have spoken to me afterwards saying they found the experience liberating.

I like working in a home environment as it’s a very personal, private space that in a way reflects the mental space these people live in. It shows what it is like to be human, and I like showing these strange sculptures made of flesh in spaces that have been arranged and lived in by individuals.

I am always keen that everyone is comfortable; I send people examples of what the shoot will be like, I’m always checking in and making sure everyone is happy. During the photo-shoot it’s just a question of overcoming the feeling of the body as a sexual thing.

These images are very similar to sculptures. Do you see your work as a practice between photography and sculpture?

I very much think of them as sculptures. When I am photographing people I look at them as a material to sculpt from. I try to pull them as far away as possible from the human body by turning them into these ambiguous shapes.

I am really influenced by sculptors, one of my favourite artists is Berlinde de Bruyckere, who sculpts the human body, although none of them are anatomically correct. Her works are made of layered wax, which bring through different colours in the skin. None of them have faces or heads, they are anonymous, but there is so much character and emotion in their poses and in the way that they are formed. To me they are very strange and wonderful.

Although in my work I am creating anonymous sculptures that are trying to depict the human body differently, many of the photographs contain little moments that act as evidence of humanity being present. One figure has a red mark on their side, which is clearly from scratching an itch. Another has the imprint from a bra. I love these little moments – they are a proof that the body has been lived in.

Photography is the only medium that allows me to sculpt with human flesh, everything else can only be an interpretation of it. I have also made two short video pieces that look just like these images but move slightly as the figures inhale and exhale. They are accompanied by a recording of the breath. The bodies look static, but then you start to realise there is movement and that you are not looking at a static image. The videos were premiered at Photofusion last May.

Is Form and Function a finished project or do you think you will expand the theme?

It’s hard to say when a project is finished. I am always fascinated with the human body and I will continue exploring it, probably not in the exact same way. It does feel as though there is some sort of end to the project now however, as the book is finished. My practice is shifting, but not moving away from the body in space.

What is your ambition with Form and Function?

I want to help people reconnect and appreciate the natural form and all its shapes. Inclusivity is very important to me. Different body shapes, sizes, ages, sexualities, genders are all included in this work and are all treated in the same way.

Do you have other projects planned? Another book perhaps?

I have things in the pipeline, but I find it quite hard to talk about projects when in the beginning stages. I would like to publish another book though. Form & Function is the first one I have made.

How did you select images for the book?

The book is made up of 74 photographs. My gallerist Laura Noble helped me with the edit, I didn’t want to include too many as that would have been overwhelming and would have desensitised people to the project. Form and Function is being sold in a number of bookshops and galleries. I am also selling it online on the publisher’s website, Stay Free Publishing.

The book comprises an essay by Laura Noble, director of L A Noble Gallery, a foreword by Jude Hull, Photographs Specialist and Head of Sale at Christie’s, and an ‘in conversation’ article with Laura and myself at the end.

—

Chloe Rosser will be doing a book presentation and signing at The Photographers’ Gallery on Thursday 30 May, 6-8pm. Free entry. Details here.

Chloe Rosser www.chloerosser.co.uk is represented by L A Noble Gallery and has recently released her book Form & Function, published by Stay Free Publishing. £35, edition of 750. It is available at: www.stayfreepublishing.co.uk