Joffrey Monteiro-Noël and Vadim Alsayed’s ‘Traque’ explores the essence of artistic flare, transforming the reality of what movement is, into a tale of creativity and curiosity. With Monteiro-Noëls background being of the theatre, it is no surprise that this creative works with the of both space and expression – Joffrey Monteiro Noël kindly took the time with Jungle, to explore these two concepts and how they work with both fashion and movement, alongside his own creative aesthetic.

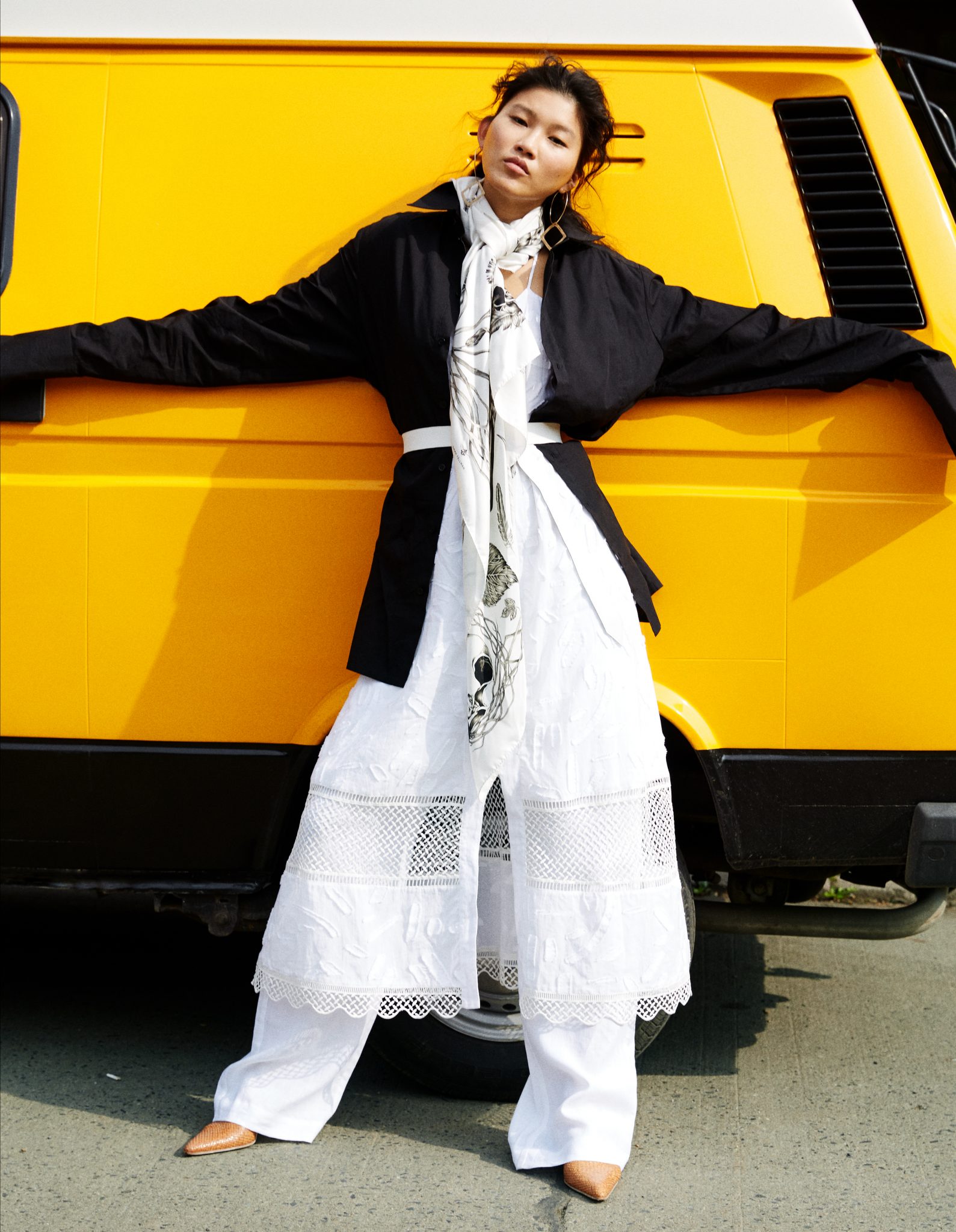

Based within a forest setting, used as a “collective psyche” that is both timeless and of “suspended time”, against a vision of one singular dancer contrasting against a group of bodies, it is obvious to see that it is not only the identification of movement that relays a story, but also the use of both colour and clothing. Monteiro-Noël shares how “The initial thought was that the garment would be a central point in making ‘Traque’. With Vadim Alsayed, who co-directed the film with me, we wanted the main character to be both part of the environment and slightly out of step from the setting. The group of men are totally included in the atmosphere as if they were themselves the forest”, Monteiro-Noël discussed how they “really liked the idea of timeless clothes. We were supported by COS and saw in the last collection this red sweater and the bomber jackets. We decided to give the sweater to the main character [Adrien Dantou] – it is a very recognizable aspect and of course the red was something that fitted with the tones of the forest but also with its notion of prey.”

In terms of a storyline development, there is an acceleration of action and course of events, as our main character is seen to become trapped by his captures, a flurry of both dance and distress heightens the despair of ‘Traque’ – the movement acts as a personification of this emotion, with Moteiro-Noël observing that “The main idea on which the film relied on, is that any movement comes from another movement. There is no movement coming from nothing. This was our first interrogation with Vadim when we were writing ‘Traque’ – how can we bring movement into a still shot? Where does the first movement come from?” it is clear that the visual sequence of movement is key to the development of Traque’s storyline -“When rehearsing with Dantou, who plays the main character, we spoke about the idea of prey and how the animalistic way of moving was at the centre of the work. We loved the idea of considering the main character as a deer. A hunted deer who stops, listens and runs… That’s why at some point in the choreography there is a position that refers to the deer’s antlers. Of course, the hunting and steps are depicted differently with contrasting rhythm and acceleration.”

Yet for the acceleration of the action, there is both a cause and effect, with a considerable dramatic effect on the audience being created – “the first shot of the film is quite long – a still 15 seconds. This shot for me is the most important as it also sums up our love for fixity and movement. Actual fixity is essential to movement; in order to exist, one does not go without the other. By beginning the film by this long shot, we wanted to put the viewer in a certain position. A position where the viewer can receive and feel the evolution of movement. Of course, this kind of long shot can still be intense, but it is a way to inform and prepare the viewer. It was essentially a way to make the audience become attentive, even if they felt it was too long, in order to follow the evolution of movement.”

In terms of creative material, ‘Traque’ is shot through 16mm film, a cause of action that Monteiro-Noël suggests as an opportunity that developed into a beneficial decision – “Vadim and I were given two rolls of 16mm film which is 22 minutes of shooting and development. We both love the aspect of 16mm – the instinctive relation with photography and to be precise, the mystery in the lights. Quickly in writing we realized that shooting with a digital camera would be easier – when you shoot dance, the temptation to have long and numerous takes comes quickly. However, we wanted to capture the ‘raw’ aspect of dance. We decided that it was better to keep this constraint of two rolls, when we went into the forest with the camera and had our first look at the frame we knew that we made a good decision.”

‘Traque’ acts not only as a tale of creative development, but also as an exploration of how the notion of movement can be revealed both through artistic acknowledgment and creative flair – the short film offers an expression of both the beauty of movement as well as the artistic use of how the medium of film can lead to, as Monteiro-Noël suggests, “total freedom.” As proven by ‘Traque’, movement is a form of creativity, and as Monteiro-Noel suggests, a creative entity in itself.