Artist: Joshua Perkins

Words: Cassandra Seidel

British born Joshua Perkin has an artistic identity which will lure you into his world. The figures in his works have their own inner dialogue and a contemplative expression; similar to that of the artist himself. Exploring the relationship between artistic production and labour work has been at the root of his practice. Joshua splits his time between working on construction jobs and dedicating himself to creating artworks in his studio in Barcelona.

His works are often influenced by his surroundings, travels and his parents’ admirable work ethic.

During this time in isolation, he finds himself in the same place where he found his love for both creating artworks and labour work; on his family farm in England. Working on the farm consistently for the past nine weeks, finding time late at night to paint in-between early wake-ups and assisting his Father with lambing. Growing up with a creative Mother and a Father who introduced him to the world of labour work and farming, has significantly influenced the way Joshua expresses himself; the merging of the two dynamics in his life.

His dedication to his practice, and his journey on his ‘artistic investigation’ has resulted in consistently creating artworks, with around 150 artworks in storage. Joshua’s story is a true anecdote to the artist who paints, not to make millions of pounds, but because it brings him great joy.

‘Over the past few years I feel proud of what I’m doing, because I feel like I am developing an artistic identity. I’m projecting what I want to paint and I feel like when you get to that stage it’s quite fulfilling.’

How are you dealing with this time in isolation? Do you feel creatively challenged or have you been working on new projects?

I don’t feel creatively challenged at all, but I’m also not working on a new project right now. For the last two years I’ve been on an artistic investigation, looking at the relationship between labour work and artistic production. I used it as the focal point for my Master’s Degree, which I finished last year. Three of the main lines of connection would be pictorial representations of labour workers, people who are working in labour work and also producing art and then labour as art. So during lockdown, I have been on my father’s farm, working full time, and I’ve had one day without working on the farm in the last 9 weeks. During these labour-intensive periods, I’m delving in my head and looking at the relationship between artistic production and labour in a strange way. I’m just considering the artistic investigation that I was already on. I’ve made various paintings since I’ve been here, in the evenings or late at night. They’ve been very aesthetically influenced by what’s around me so lots of them feature sheep, shepherds and shepherdesses.

It seems as though your surroundings have naturally integrated into your work. Do you feel that this has made your work different to how you would usually create in Barcelona?

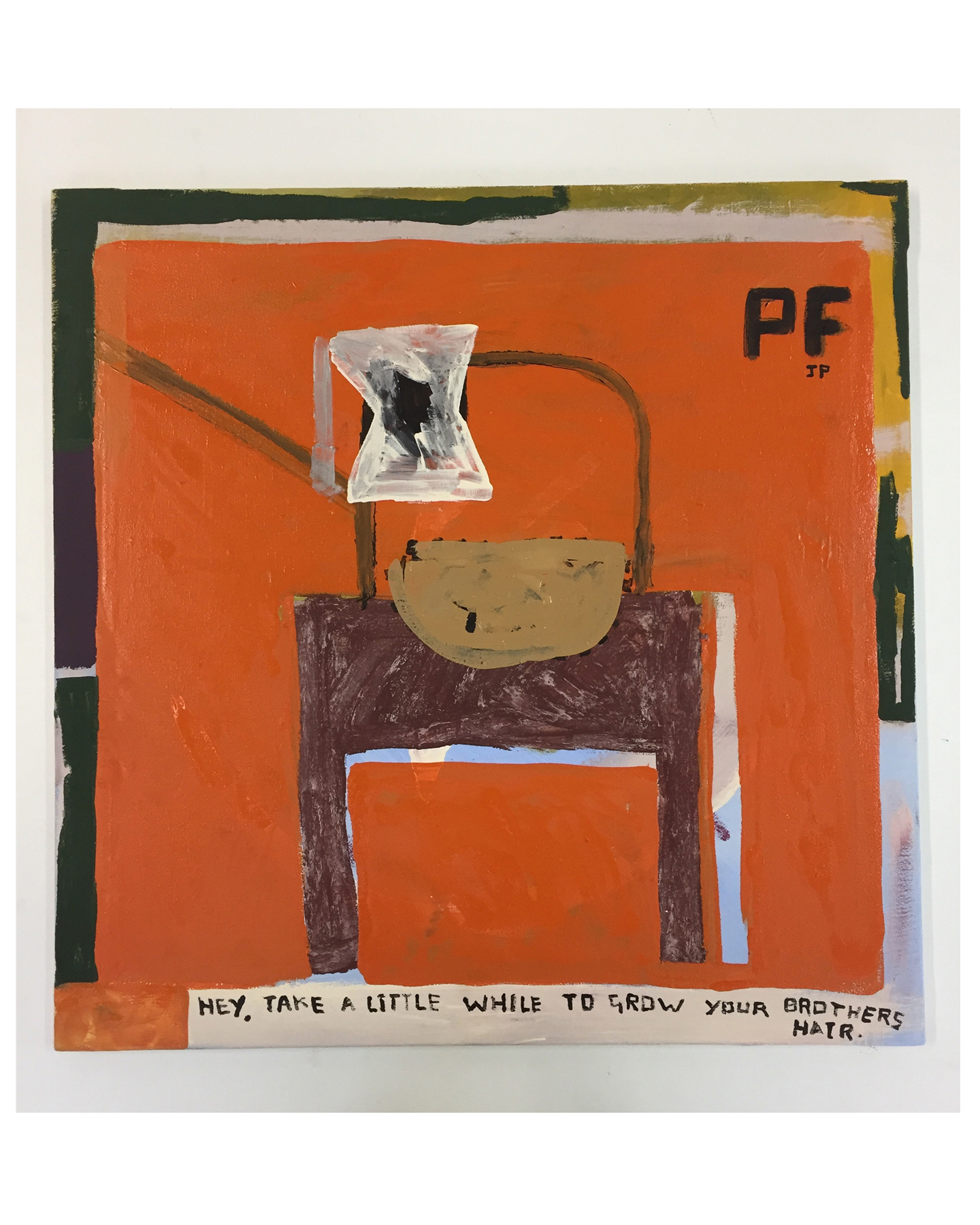

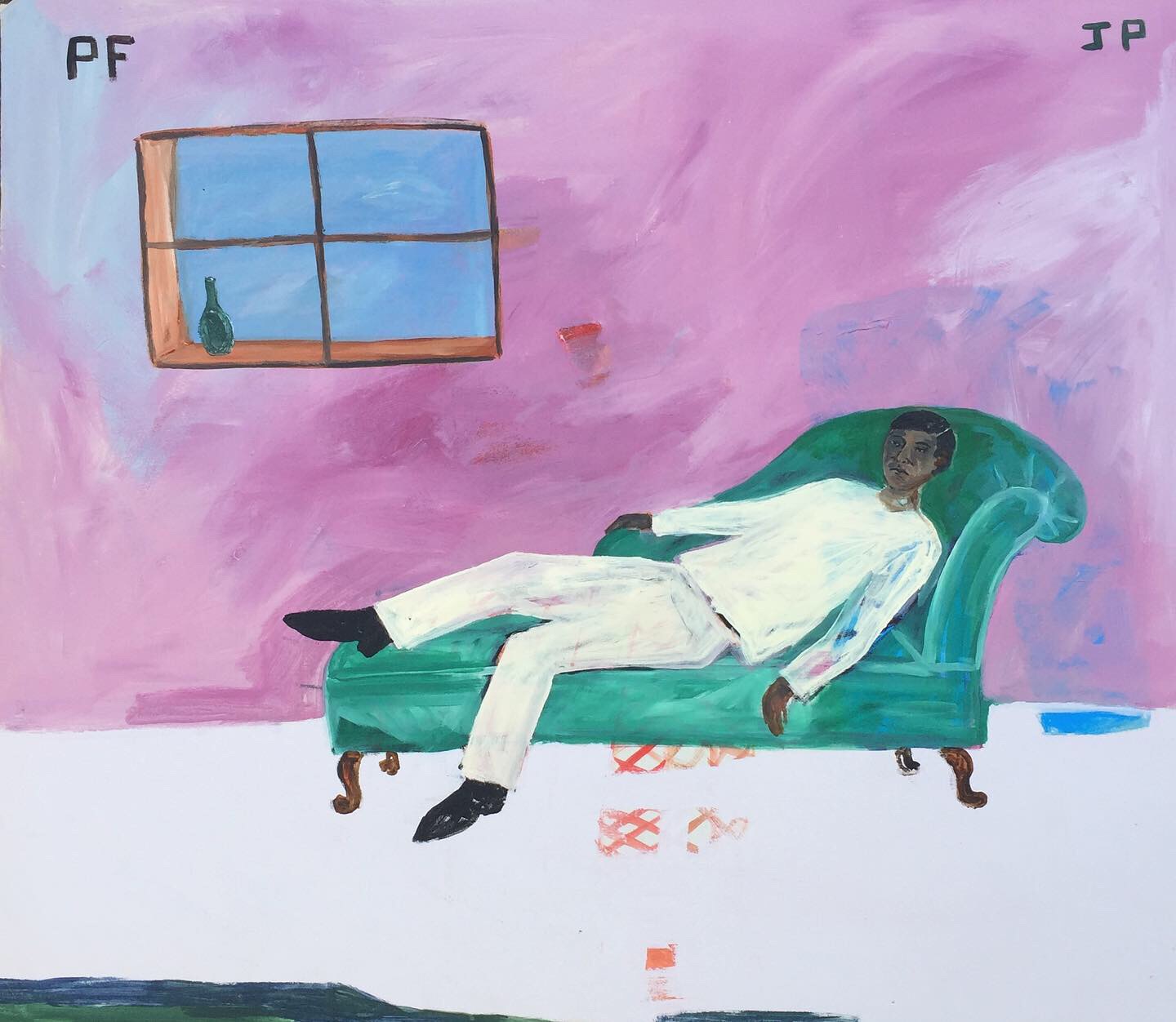

I mean, my surroundings have always integrated themselves into the artwork. Your identity is so integral in your artwork, for example the ‘PF’ on the paintings stands for ‘Park Farm’ which is where I am right now, and it’s the root of everything. My dad’s work ethic and his approach to farming in general is something that has always stayed with me since I was a little kid. That is one of the things that motivates me to be prolific when making artworks, and to try and keep as busy as I can. Artwork and labour work both turn into spacial interventions that can potentially generate dialogue around certain subject matters.

So then would you say your time in Spain has made your work reminiscent of the country’s culture and traditions?

There are a few paintings that I have done over the years which are explicitly affected by my surroundings; featuring flamenco dancers and bulls. But apart from that, I find it difficult to detach my feelings, state of mind and knowledge from paintings because I’m not someone who paints super fast. Usually they do take me quite a while and I’m usually going over layers and rubbing out stuff. It’s quite a contemplative process and in that process your mind is wandering and I think that creeps into the work. Different things inspire you as well, whether it be the colours or specific scenes. My more figurative works are collages of information and images either mentally retained or photographed or cut out of things, they’re all sort of mix matches of various things.

How does your creative process unfold from start to finish?

There’s always a start that’s very laborious and enjoyable, that is making the frames and stretching the canvases. It’s also nice to get ambitious with the scale and structural forms of the thing that you’re going to paint on. Image making wise, it’s different every time. Sometimes, I’ll just start painting a person and everything goes from there, or other times I will have a visualised backdrop. For example, I have in my mind a very clear image of what I want to paint on one of the triptychs, which is a collage of things I’ve seen while working here. A lot of times I will finish a painting in a week and put it into the pile of 200 paintings that no one ever sees in my studio. Occasionally there will be one or two paintings that I change three or four times a year, or finish and put aside and then a year later add in something so small and then think it’s finished. It’s difficult to know when it’s finished.

Would you say that the ideas around work and labour are integral to who the person you are today?

Yes, I grew up on a farm and my dad had us out working from when we were super young and my Mum was very hardworking, but also very interested in all things artistic. She was very into gardening and garden design and very conscious of interior spaces. What she could do with these spaces was unbelievable. When we moved into this farm, the place was a total ruin and she just made it so beautiful, and on top of that she was making her own artworks. She was a massive inspiration for me and encouraged me to start painting so I could get a scholarship to a really good school. She would take me out and we would sit in the fields together doing watercolours of the bales and tractors, with my dad working in the distance with the sheep. I’ve still got some of those paintings around the house. Now my life is a fifty – fifty split between various labour works on farms or on concrete and then dedicating the rest of my time to painting.

It seems as though art has always been a part of your life. How did you find your way to create your own practice?

I’ve been into painting constantly since I was eight and quite consistently made artworks. Then in my early 20s I got more into literature and exploring new places. I forgot about making artworks so ‘full on’. Then, when I started getting back into it, I felt sort of lost. I never had any formal art training and in my naive mind I thought I needed to have some deep meaning behind what I’m doing; to validate it somehow in a social political context, to make it worthwhile. Some of my main artistic aesthetic influences would be people like Paula Rego. I feel what’s so powerful about her painting, is that she’s got this dialogue that it generates, that is about these social political issues that are so important and need to be talked about. Kerry James Marshall is another influence of mine to explore racial representations in artworks. I started on my own artistic journey trying to clutch onto anything that I could to give my work some sort of deeper meaning, to move it away from a superficial, just for aesthetics. The construction jobs took me all over the world building skateparks – Iraq, Nepal, Palestine. These travels have brought aesthetic influences into my work and made me want to merge the representation of human form into something that is generalised, so that everyone being represented is the same person but also ‘the other’. All the people in the works are invented, more or less. Sometimes I look at photos I have taken for ideas, but generally it is invented. I want all the people to be unrecognisable, where you can’t pin point a specific geographical location to each of the individuals, according to their skin colour or dress code. They all turn into this atemporal being from everywhere and nowhere; to try and get away from ‘the other’ in works. I suppose they all have an expression which I guess reflects my general expression, they’re all semi contemplative or semi fed up.

Many creatives feel immense pressure to constantly be creating new work. Do you feel pressure to keep up with the rapid pace of the art markets?

I don’t feel that pressure at all. If I felt that pressure I’d probably stop, because I hate pressure, but I feel proud of the work ethic that my parents have drilled into me. The balance between earning a steady income through labour jobs and producing artworks is integral to both of those separate facets of my life. Both facets motivate each other. I always go into a construction job ready and keen to start work and get on the build. I love welding and woodwork. And then after a few weeks of long days I start to miss painting. That becomes a perpetual cycle and I don’t intend on changing the cycle. The next project is to find a ruin in rural Spain and convert that. It’s all the same, it’s spacial intervention and all a contemplation on aesthetic.

I’m not really in the art world. I currently don’t have representation and I’ve never tried or been approached by a gallery. Last year I made seven skateparks and had seven or eight exhibitions, so it was a pretty busy year. Most of the exhibitions are DIY – they’re all friends who have spaces and want to put work in them.

Do you enjoy collaboration?

Yeah totally; that’s a whole other aspect of my artistic investigation – collaboration and working in a team. That’s something that I really enjoyed doing last year with Carolina, who is a floral designer. We had ceramics, which is the most ancient product of labour work and also one of the most ancient art forms. She’s also a Chilean woman and I’m a British born male and that fusion of cultures and genders was something nice to work with. I have another collaboration loosely planned for this Summer, and the person who I’m collaborating with doesn’t really know about it yet and I don’t know if they exist, but I’m sure it will happen.

Do you feel challenged by the commerciality that comes with being an artist today?

I don’t really know much about how the art world operates, and I semi don’t care. I just want to make paintings and have works that I delve back into. At the moment I couldn’t be more content with how it’s going with the artworks. I sell a few here and there and generally get to meet the people who want them. It’s a privilege to meet someone who wants something that you made. I’ve got food in my belly and a roof over my head, so why would I want to sell artworks for millions of pounds?

I feel like being an artist is such a long journey on various levels. Your thought process, the way you approach it, and obviously your product. Over the past few years I feel proud of what I’m doing, because I feel like I am developing an artistic identity. I’m projecting what I want to paint, and I feel like when you get to that stage, it’s quite fulfilling.

Joshua’s work can be found on his Instagram: @jushuaperkin