When Portrait of Britain announced that it was returning for a second year, the open call for submissions was answered by nearly 8000 photographers, of both the professional and the amateur variety. The breadth of response speaks volumes of the prestigious cultural event’s potential for broadening arts engagement across the UK. Not only is Portrait of Britain open to all but it has broken free of the restrictive confines of the art gallery.

Based on the founding principle of inclusivity, the 100 winning entries were beamed onto screens up and down the UK. Large public areas like shopping centres and train stations in locales such as Leeds, Glasgow, Southhampton and Cardiff were graced with the Portrait of Britain’s presence. With the UK arts scene coming under fire for a decidedly London-centric focus, it is vital that important exhibitions follow Portrait of Britain’s example and open their doors to a much wider audience.

This ‘for the people, by the people’ ethos, is exemplified by the diverse characters featured in the winning portraits: from public personalities like Skepta and Tom Stoppard, to individuals from remote areas of the nation which can often be over-looked. Jon Tonks, for example, showcased ‘Ruth & Marmalade’, a portrait of an Inner Hebrides islander with her pet falcon, capturing his subject’s vibrant personality and emphasising the stunning beauty of the area’s natural landscape. Rick Pushinsky, on the other hand, presented a portrait of prominent British artist Tracey Emin, which through capturing her in a domestic setting, sought to emphasise the woman behind the icon.

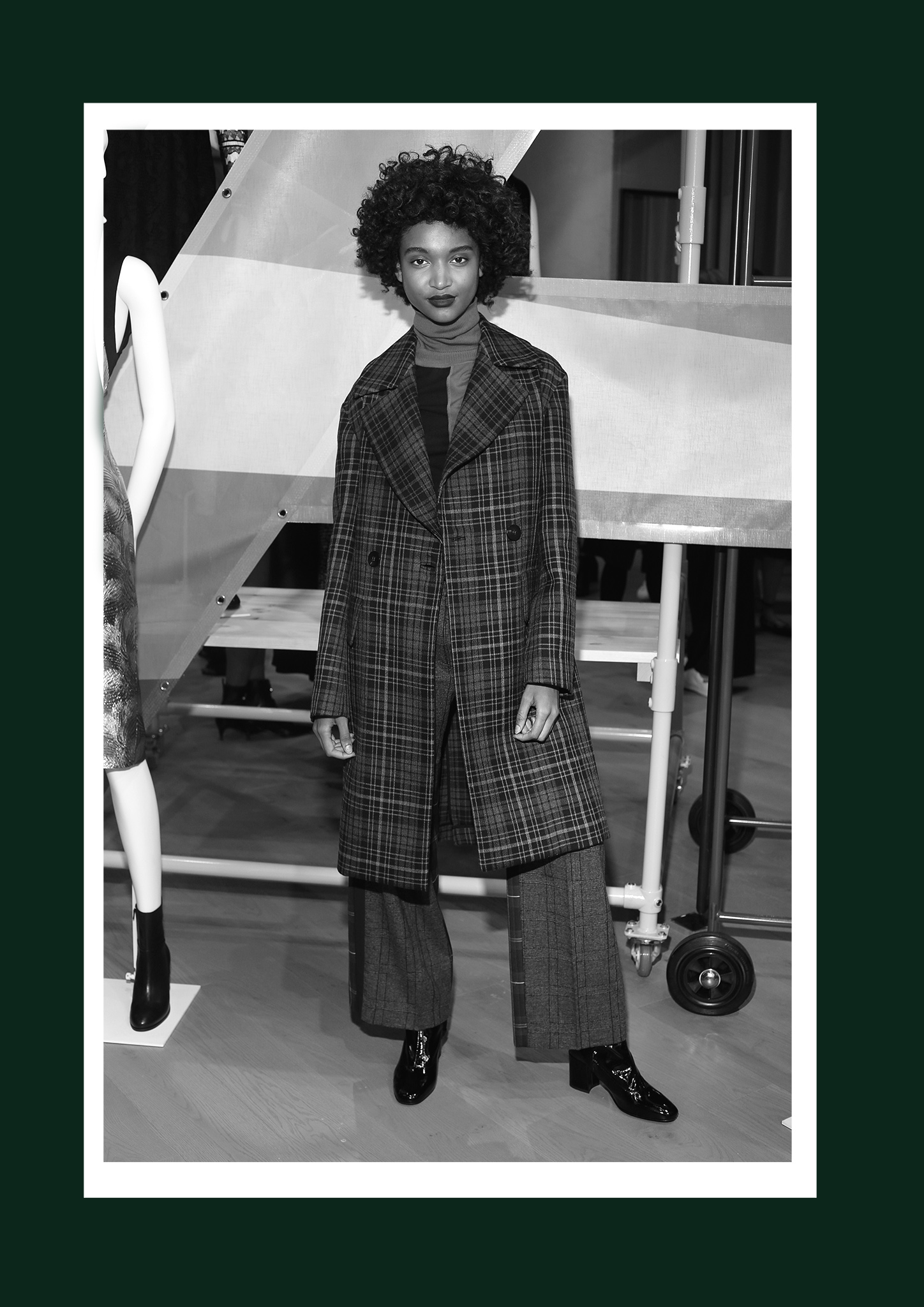

The renegotiation of personal boundaries emerges as a recurring theme in the exhibition. For example, John Russell’s winning entry, ‘Selfie’, depicts the collision of public and private enacted via social media. Presented in stark black and white, the unknown subject snaps a self-portrait whilst simultaneously being captured by the photographer’s lens. This serves as a profound commentary on our Instagram culture: the sharing of intimate details to a potentially global audience, one who we can never control or see in their totality.

Elsewhere, Jørn Tomter presents ‘Waiting for mum’, a charming group portrait which captures siblings outside their home in Clapton, London. Here, the relationship between our collective and individual identities is explored. The way the children sit on the front steps communicates a sense of familial harmony and order, with each individual positioned in a similar manner and all compliantly facing the camera. However, the photographer also manages to capture the distinct identities of the children within the family unit, documenting the differences of facial expression and body language. Tomter’s image, and the thoughts it provokes, is a particularly fitting emblem of the exhibition, which strives to demonstrate how individual narratives feed into our overarching national identity.

With such strong driving principles and the support of Nikon and JC Decaux, we can only hope the exhibition returns for a third time in 2018.

Words: Megan Wallace

Editor: Emma Bourne