November 2016. In the main hall of London’s Barbican Centre, a venue with a rich and ongoing relationship with jazz music in all its forms, saxophonist and composer Wayne Shorter is performing to a rapt audience seemingly all well aware they are in the presence of greatness. Shorter and the other members of his quartet–Danilo Perez on piano, John Patitucci on double bass, Brian Blade on drums–are ushering out the final night of the London Jazz Festival, an annual event which brings together many of the jazz world’s great and good for a ten-day feast of music. Switching between tenor and soprano, Shorter and his saxophones lead the audience–and his band–on a spellbinding musical journey, Perez, Patitucci and Blade all still clearly relishing the formidable task of remaining in sync with Shorter’s trademark improvisations. By anyone’s definition, this is jazz.

November 2016. In the main hall of London’s Barbican Centre, a venue with a rich and ongoing relationship with jazz music in all its forms, saxophonist and composer Wayne Shorter is performing to a rapt audience seemingly all well aware they are in the presence of greatness. Shorter and the other members of his quartet–Danilo Perez on piano, John Patitucci on double bass, Brian Blade on drums–are ushering out the final night of the London Jazz Festival, an annual event which brings together many of the jazz world’s great and good for a ten-day feast of music. Switching between tenor and soprano, Shorter and his saxophones lead the audience–and his band–on a spellbinding musical journey, Perez, Patitucci and Blade all still clearly relishing the formidable task of remaining in sync with Shorter’s trademark improvisations. By anyone’s definition, this is jazz.

Shorter came to the fore during a golden age for jazz music. From the late fifties to the mid-sixties, the likes of Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Charles Mingus, Art Blakey, Ornette Coleman, Dave Brubeck, Sonnie Rollins, Herbie Hancock, Dexter Gordon, Lee Morgan, Eric Dolphy and Shorter himself were responsible for what many see as the greatest jazz albums ever made. So seminal was this period of time for jazz, it remains an essential reference point for people looking to define what jazz is. Whilst this is wholly understandable – some of the albums produced during that time stand amongst the greatest records of all time, jazz or otherwise – the shadow cast by Davis, Hancock et al still looms large. So where does that leave jazz today?

Aged 83 at the time, Wayne Shorter’s aforementioned headline performance was the latest example of the London Jazz Festival looking to artists from that golden era of jazz to attract modern day audiences. Ornette Coleman, who sadly passed away in 2015, was 81 when he appeared at the festival in 2011; Sonny Rollins, who performed there in 2012, was 82; and this year, Herbie Hancock is the festival’s big name, a relative spring chicken at 77. Absolutely nothing should be taken away from those still performing; to a man, each and every one of them is as great today as they have ever been. Of that lengthy list of great musicians above though, Shorter, Rollins and Hancock are the last survivors. There are of course numerous younger jazz artists, amongst them the hugely successful and acclaimed Esperanza Spalding and Brad Mehldau, who sell records and regularly perform live. When it comes to widespread profile though, are the likes of Spalding and Mehldau enough to keep jazz alive? And does it even matter anymore?

“I remember Pete King saying the same thing to me; ‘All the legends are dead! How are we going to carry on?’” says Nick Lewis, Operations Manager at the world-famous Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club. “Well, it hasn’t happened yet.” As a central part of the music programming team, Lewis, who has been at Ronnie Scott’s for over a decade now, is responsible for ensuring that the club remains busy by presenting the very best jazz and jazz-related music they can. Lewis was drafted in during a major transition for the club, when Pete King – who had founded the club back in 1959 along with his good friend, jazz saxophonist Ronnie Scott – sold the club to its current owner, theatre impresario Sally Greene. “It wasn’t the easiest changeover to be honest. This place was always seen as a bastion of what’s ‘real’ as a jazz club. Before, it was seen as a place run by musicians for musicians and the new owners tried to make it a business that would pay for itself. Beforehand, the sums didn’t necessarily stack up; now they do. It will never stop being that age old debate between art and commerce though. I could name you a 100 bands who could sell out the club and the audience will be eating fillet steak and drinking champagne, but we know that’s not right spiritually for the club. We have to balance that with more cutting edge bands that attract a crowd who drink water, or beer if we’re lucky.”

For an establishment as renowned as Ronnie Scott’s, finding artists eager to perform there is never a problem, but there is a lot more involved when it comes to creating the best possible programme than merely waiting for musicians to get in touch. Lewis cites American saxophonist and composer Kamasi Washington as a prime example. “He’s one of the leading lights of the cutting edge scene, signed to a label called Brainfeeder who have Flying Lotus, Thundercat, all those guys. He’s very much a part of the current LA scene. Those guys don’t come to us; we have to try to convince them to perform here. It’s a constant balancing act of trying to get stuff you know is right and trying to raise the game, getting big name artists as well, and also representing young up and coming British artists.“

All of which sounds fairly positive for the ongoing evolution of jazz music. Whether that message has made its way out to the wider music-loving populace is another matter though. Which begs the question, does jazz have an image problem? “It’s difficult for me, because I’m so in the bubble of jazz,” explains Lewis, “but I am aware that it’s got this stuffy, impenetrable feel to it, and I’m all about breaking that. I just think it’s fantastic music that deserves to be experienced by everyone, no matter how old you are or how much money you have. There’s still a desire – more than ever a desire in fact – to see live music and live jazz. There are more bands than ever doing interesting things, there are more audiences than ever. I think the internet has opened up people’s minds way more than pre-internet. The average 20 year old now knows way more about music than when I was 20. I’m in the lucky position where I get to programme for the club but I also get to challenge people’s perceptions of what a jazz club is. I was the same; before I started here, my perception of a jazz club was ‘stuffy place where you’ve got to wear a suit and tie and sit there and not talk, just click your fingers or whatever’. There’s an element where it’s become part of an aesthetic; when jazz is played in a coffee shop, when it’s played in Starbucks or in some swanky members club as acceptable background music, or it goes with a high-end whisky brand, and it’s all a bunch of toss. That has kind of lost the essence of what it’s all about.”

Going forward then, Lewis is someone clearly in a position to comment on the health of jazz music and, for him, the future looks bright. “Jazz, and music in general actually, is in a really good place in this country right now. Someone once said that jazz should be a reflection of what’s happening now. From what I can see, a lot of the young lions of the jazz scene now, they all get that. They’re not trying to do ‘Take the A Train’ from the 1930s, they’re trying to do the best representation and imitation but also putting their own spin on all the music that they’re hearing now, all the influences that they’ve absorbed. Blue Lab Beats, they’re what you might call on the fringe of the genre. They’ve certainly got jazz in their music; there’s improvisation, but they also have a drum machine and hip hop and dubstep and soul, a lot of old school De La Soul and A Tribe Called Quest in their music. I think the new generation, when it comes to the jazz scene, they’re well into their old school Art Blakey and their Max Roach, but they’re also into their Fela Kuti and their Afrobeat and hip hop meets jazz from the nineties, you know? They’re into dubstep and they’re into grime. That’s a marked difference from, say, the jazz movement of the eighties, Courtney Pine, artists like that. They were fantastic jazz musicians but they were very much in the jazz mould, whereas the new guys, they don’t have any boundaries. Jazz is the core of what they do, but they take on influences from all over.”

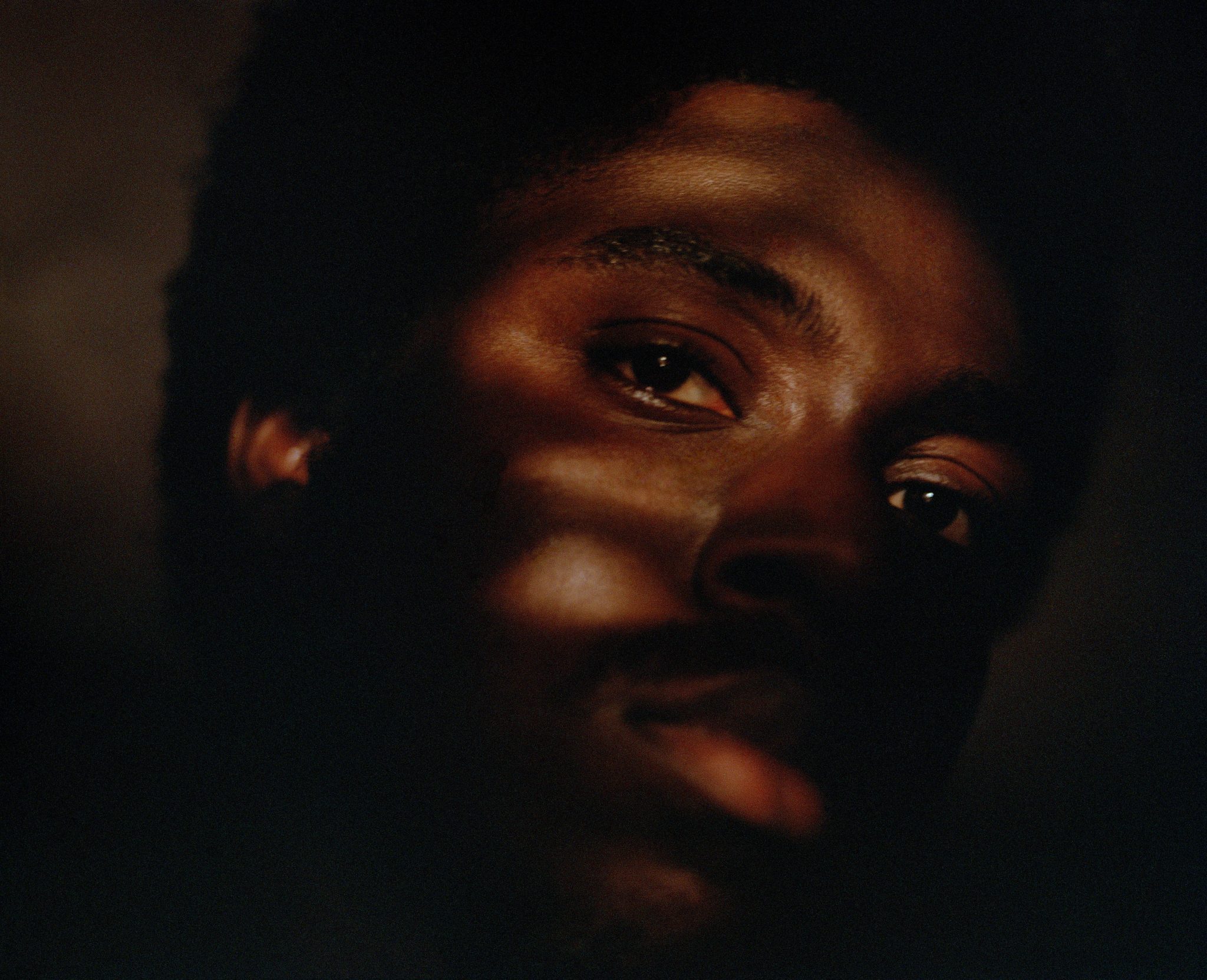

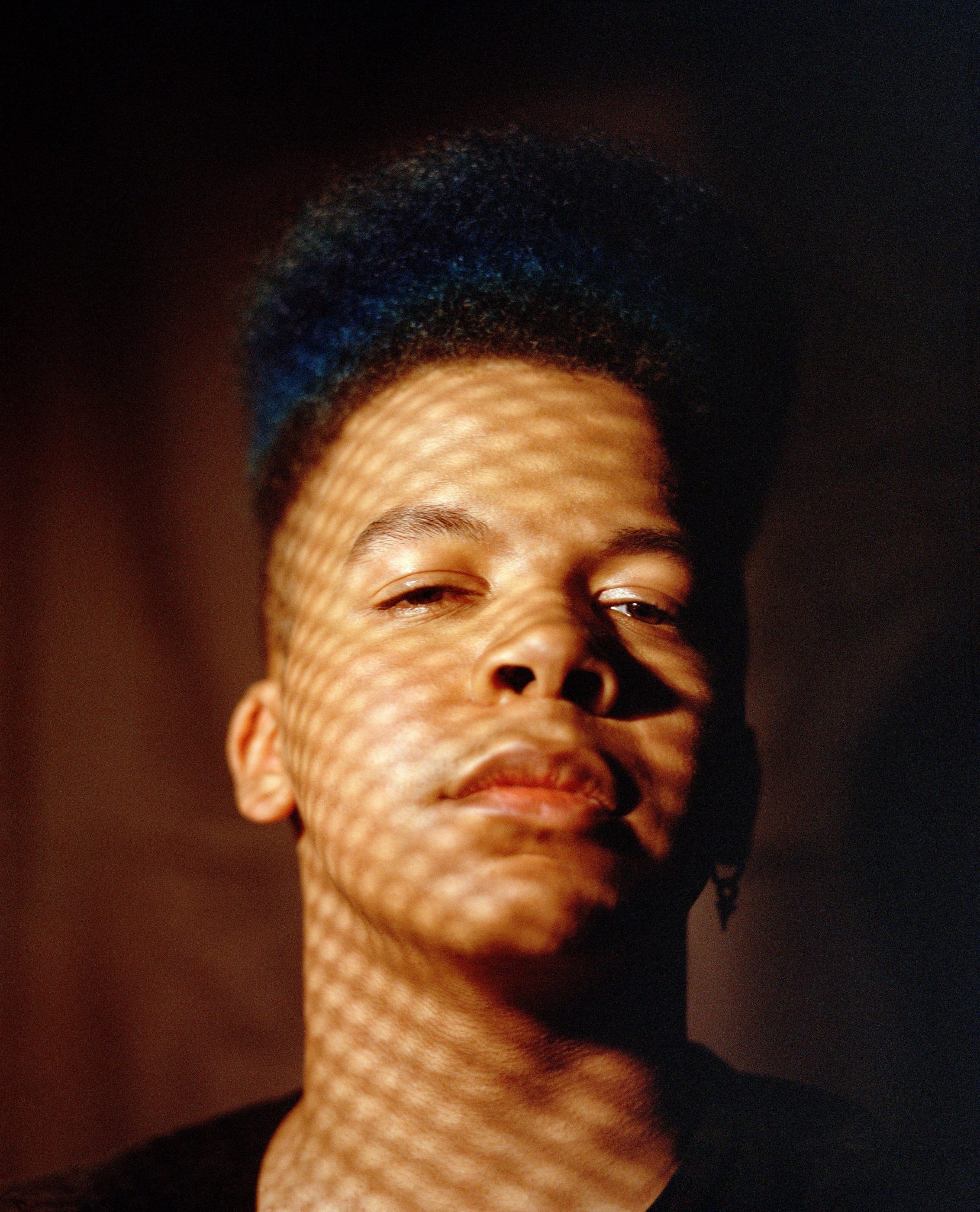

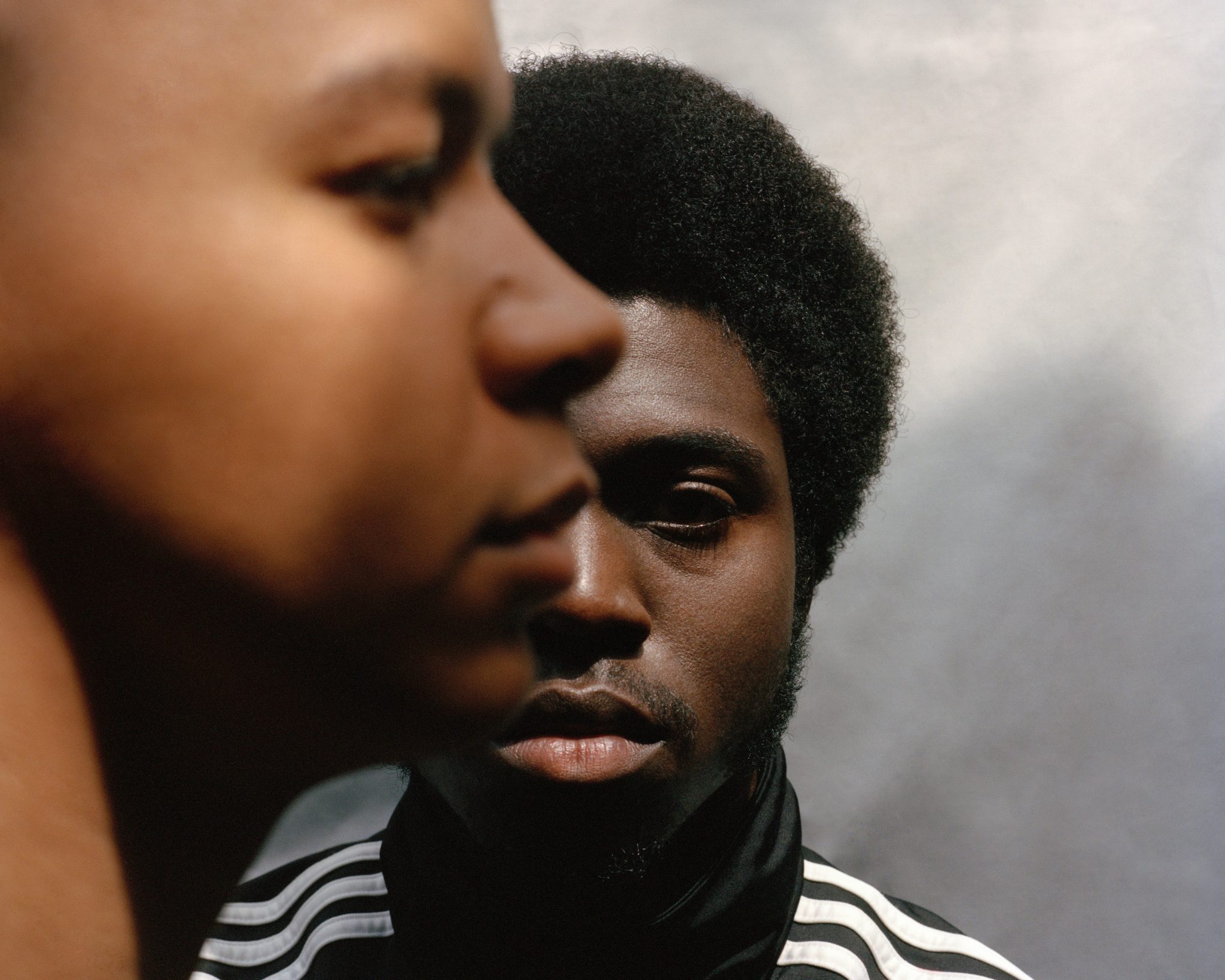

The same evening I speak to Lewis, in the welcoming confines of the upstairs bar at Ronnie Scott’s, Blue Lab Beats play the main room downstairs as the featured act of the Late Late Show, a relatively new element of the club’s programme. Already proving popular with audiences looking for some late night live music, the shows offer the club the perfect opportunity to promote some of the newer acts Lewis is talking about. Blue Lab Beats, comprised of musical duo Mr DM and NK-OK, aka David Mrakpor and Namali Kwaten, fit that profile perfectly. Still relatively young–Mr DM is 23, NK-OK 19–the pair have already garnered a considerable amount of respect on the live music scene in London. They first started working together following a chance meeting at Belsize Park’s Weekend Arts College; NK-OK, who was studying music production, was sat with friends in the lunch hall, playing them some of his music. “Mr. DM walked past and kind of said ‘I like what I’m hearing; I’m rehearsing just down there if you want to come check that out’,”recalls NK-OK. “I heard him play and was like ‘I need to work with this guy straight away’.”

Raised on a musical diet of John Coltrane and Charlie Parker thanks to his jazz-loving grandmother, NK-OK started to really take notice of that type of music in his early teens, along with Stevie Wonder and rare groove courtesy of his mother, a former DJ. For Mr DM, it was the purchase of a Yamaha PSR 340 electronic keyboard by his parents – themselves fans of Oscar Peterson, Sarah Vaughan, Duke Ellington – that got him hooked. “Initially, it was for them to try out because they were having lessons,”he explains. “They went out one day and when they came back, they saw me messing around with it and were like ‘Let’s see what happens’. The next year, I started taking lessons; I was really getting into it. Then when I was about seven, I started getting into drums a little bit. When I was having piano lessons though, my teacher was trying to teach me to read charted music and I’d hear strange noises in the other rooms and wonder what it was. It was like drums, guitars, bass. That would distract me because I was thinking I wanted to get involved in that.”Mr DM would go on to learn guitar, bass and later the vibraphone – or ‘vibes’ as he refers to it – whilst studying a BA Jazz course at Middlesex University.

Another institution that played an important part in the development of both musicians (though they attended at different times to each other) is Tomorrow’s Warriors, a jazz music education and artist development organisation founded in the early nineties by Janine Irons MBE and Gary Crosby OBE. “It encourages young musicians that want to play jazz, free of charge,”explains Mr DM. “Gary Crosby; without him I wouldn’t really be playing to be honest. If I hadn’t gone there, I don’t know what would have happened to my music career. He’s one of the major people I have to thank.”For NK-OK, his time at Tomorrow’s Warriors was challenging but ultimately just as rewarding. “If I heard a solo, I would get it but I wouldn’t understand the language. At the beginnings of classes, they’d be like ‘Oh, you like this polyrhythm or this time signature? OK, we’re going to chuck that out of the window. You’re going to learn how to improvise today. There won’t be any charts, you’re learning the tunes’. If it was a drum teacher, he’d be like ‘OK, we’re going to teach you a few drum licks’, everyone would be watching, he’d do a two to four bar drum lick, then he’d be like ‘OK, for the people who aren’t drumming, clap the rhythm that I just did’, that kind of thing. It was more ear training than just looking at it on paper. They were against that, literally. From that, it made me listen to solos so much more. It went from someone playing to someone talking a certain language, their own language kind of thing.”

As pointed out by Nick Lewis, whilst Blue Lab Beats should not be defined as out-and-out jazz musicians – something they themselves are keen to emphasise – jazz is very much a part of what they do. So how do they define what jazz is? “It’s a way of expressing yourself through a musical instrument,” offers Mr DM. “Yeah, what you feel, what you’re thinking at that time,” adds NK-OK. “When everyone’s communicating and the vibes change, just like they would in a conversation, but with music. If you’re listening to, like, a John Coltrane track, he’s leading the conversation, then he’ll let someone else take the lead when they’re doing their solo and he’s letting that conversation breathe and go somewhere else, then he brings it back round with the main melody line that he put down at the beginning. That’s when jazz, and music, is just beautiful.”

When it comes to considering the suggestion that jazz may be suffering from an image problem, NK-OK lays much of the blame at the feet of the mainstream media. “The roots of jazz are from a time in America when politics surrounding African Americans and other races were really, really bad. While that was going on, people wanted to use gospel choirs, instruments etc. to express themselves. Putting that pain through an instrument and people trying to bond through music, like ‘Let’s just be together, we’re all human’, and being musicians they wanted to tell it through their instruments. I think what happened is that big record labels thought ‘Oh, OK, that’s the big thing on the scene’; it’s happened with hip hop, with R n B, with blues. Big companies love doing that, finding the thing that’s hot at that moment. It’s like making it into fast food. What’s an easier listening option? But this music, you have to process it, you have to listen to each line. For them, it’s about making it obvious. It was there for that original reason, for telling stories. With imagery as well, from a commercial angle, you just think of people in suits etc. Our generation, our group, we all care not just about sound but about the image as well.”

The group of musicians NK-OK refers to include artists such as Nubya Garcia, Moses Boyd and his band The Exodus, Shabaka Hutchings, TriForce, and Ezra Collective, many of whom Mr DM and NK-OK know from their time at Tomorrow’s Warriors and who they have since gone on to collaborate with. Amongst others, it is this group of musicians – young, talented, heavily influenced in various ways by jazz – to whom the torch has been passed. To that extent, whilst jazz may well have shifted considerably over the years, it remains as vibrant and exciting as ever. As illustrated by those who live and breathe it, jazz is all about expression, creativity, experimentation, evolution. In short, everything great music should be.

Purchase Edition 03 here.

Photographer: Bex Day

Fashion Editor: Daniela Suarez

Music Editor: Philip Goodfellow

Grooming: Violet Zeng

Post production: Anthony ‘John’ Sayer

Photographer Assistance: Daniele d’Ingeo

Words by Philip Goodfellow

With special thanks to Ronnie Scott’s