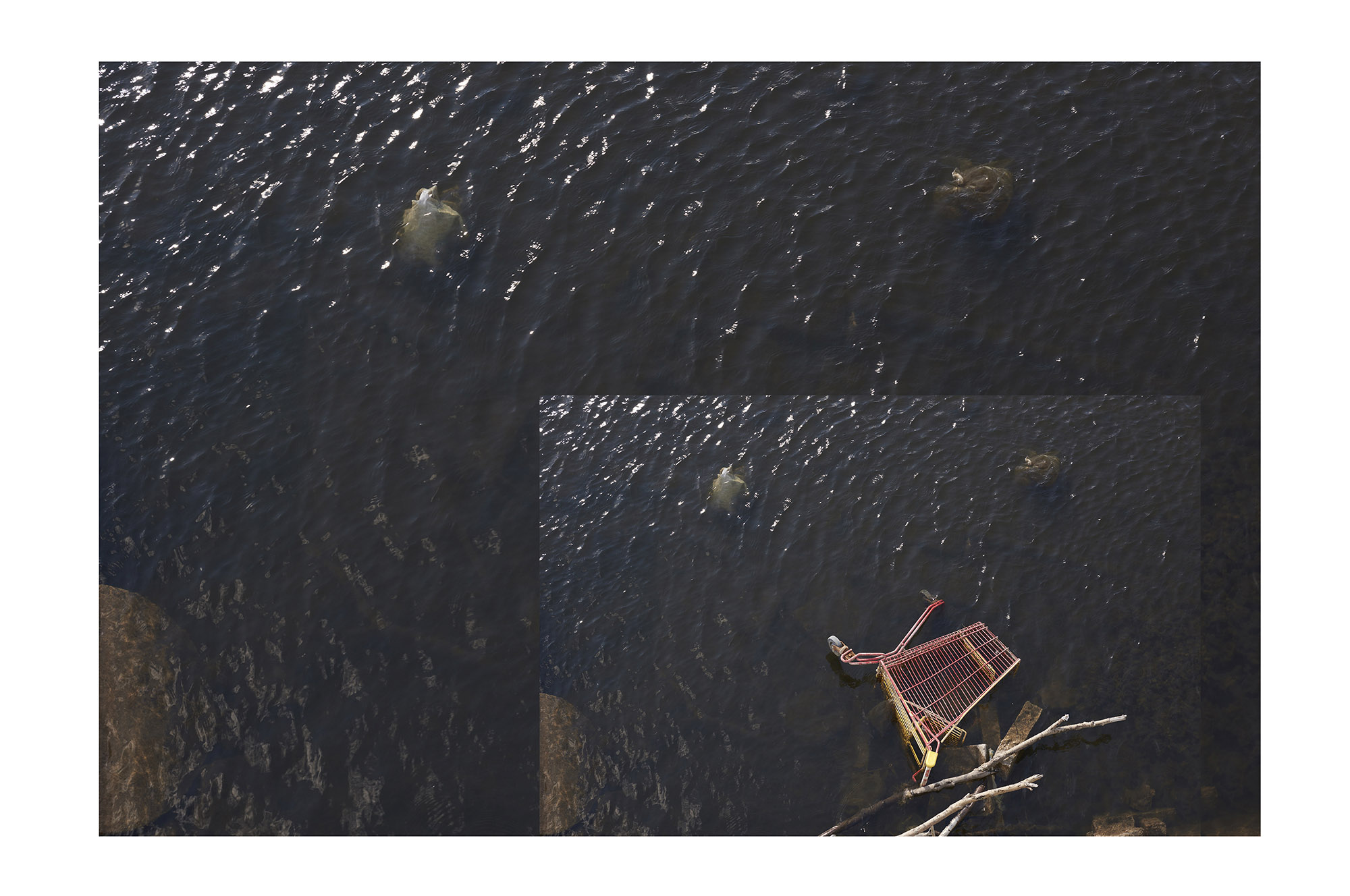

Intrigued by the mythical stories of the Estonian landscape, artist Tanya Houghton travelled across Tallinn. Lakes, forests, coastlines and ports; continuously surrounded by the downpour of rain Tallin turned to her camera to capture and later reflect on her experiences.

So tell me, what inspired you to travel?

I was invited to undertake an artist residency by the team from Urbiquity Urban Lab. I have been fortunate to travel a lot for work but Estonia had never been on my radar. It was the perfect opportunity to immerse myself in a new city and learn of a new culture that I had no prior experience of.

Estonia sounds like an interesting place, what was it like to travel across Tallinn?

Tallinn itself is an interesting city, a mix of Scandinavian and Soviet history, dual cultures live in different zones of the city with both Estonian and Russian languages being spoken. As well as structuring of the city, the Soviet past is still prevalent in the stories told. Geographically Tallinn sits on the Gulf of Finland and is surrounded by beautiful forests, lakes and neighbouring Islands, making it an interesting place to work.

Due to the nature of my practice I walk where I can and this suited the city. I tend to work broadly when compiling my narrative, collecting images and objects as I travel and explore a space.

The title ‘The Tides That Bind Us’ seems almost ironic, given that it suggests a communal experience when the photos that compose the series seem to take isolation as a central theme. How do you view this?

The title refers to the stories that bind us together, generational tales passed on, the unseen lines and collective narratives we share.

Do you think the image of water as a perpetually changing, shifting compares to the current pace of contemporary society?

I think that’s a really beautiful analogy. We live in a world where nations are desperately trying to keep hold of their borders, harping back to old ideologies of colonialism and imperial reign, which are so arrogant and outdated. We live in a world of constant flux and at the moment we are experiencing the biggest movement of people since World War 2.

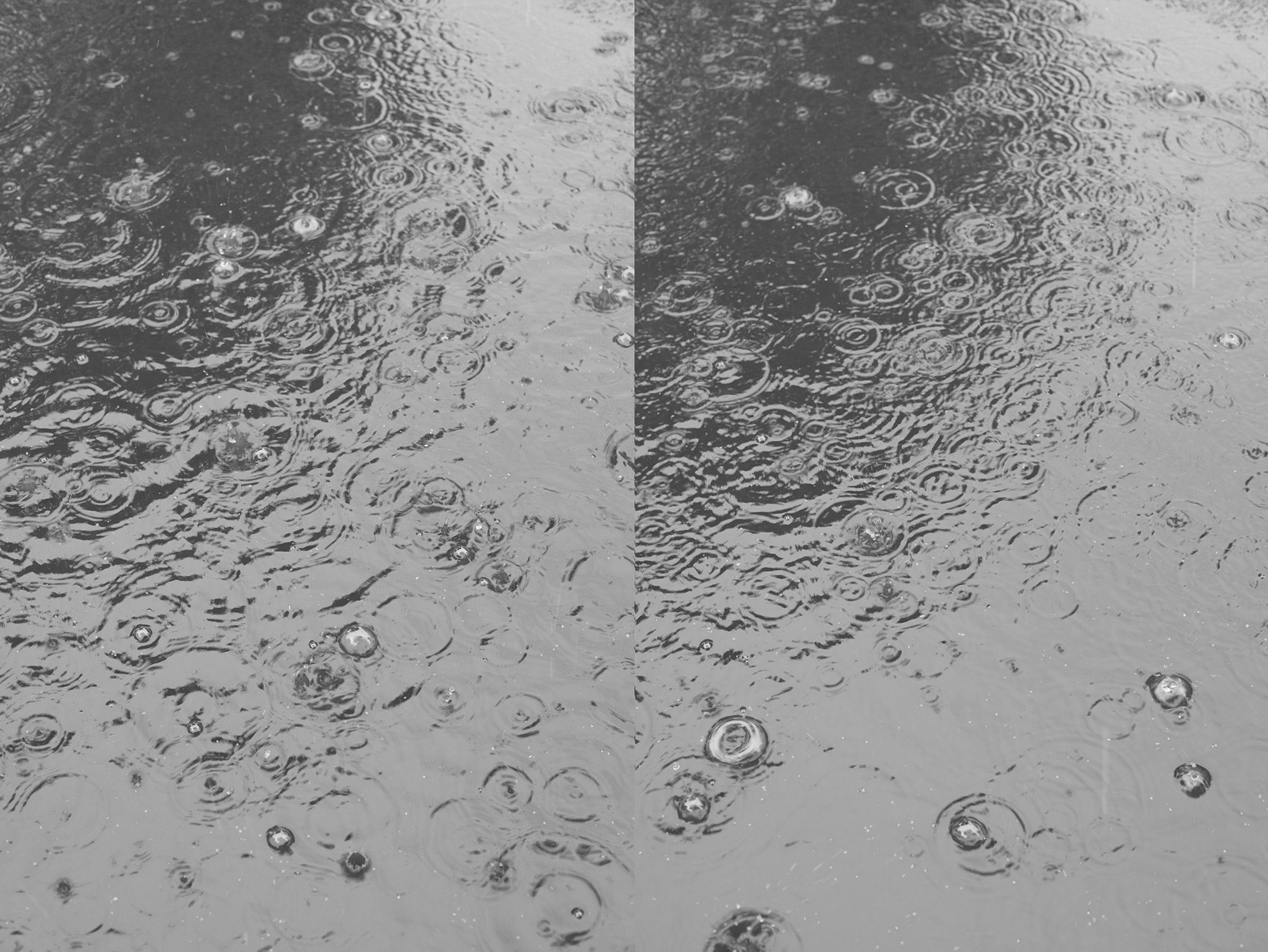

In addition to bodies of water, this series includes images of rain. What does this element symbolise for you?

The image of rain in the body of work is more a personal joke to myself and those that I met during my time in Tallinn. It rained relentlessly whilst I was working there while the rest of Europe experienced a heat wave. Due to the nature of my practice I was walking for eight hours a day, mostly in torrential rain.

This image also refers to a Poem I discovered during my time there by Estonia poet Hasso Krull – “There Are Holes In The Road”. Here he talks about walking and the holes in his shoes, the holes in the road, and the holes in the rain as the rain falls into water.

I also noticed you use both black and white and colour images in the series…

Yes, photography is still a relevantly a young form of high art compared to other mediums. It seems to come with its own set of rules enforced by the old traditions of the practice; “you should shoot film, you should never mix colour and black and white, one camera is better than the other” etc.

I originally trained in film and then spent 10 years working as a digital technician. I shoot both film and digital, I mix colour and black and white, I play with scale and exhibition format and mix still life with landscape. I have a huge appreciation for the photograph as an object in itself and approach the medium in playful response against the old traditions of the practice.

It seems that a recurring theme is how tourism is changing Estonia (as suggested by images of tourist boats coming in to port) – how do you feel about this?

For me the ferries acted on a much more symbolic level triggering stories of the mass Soviet deportation of people of Tallinn in 1941 and 1949, and the huge wave of Estonians that fled the city to avoid this enforced deportation.

I wanted to experience two things. One to gain a sense of what it was like to see the city disappear from view over the sea, a view that would have been shared by so many of the people deported. Two to experience some form of tourism to do with sea travel.

To achieve this I travelled to the small Island of Naissaar (translated as The Women’s Island) just off the coast of Tallinn to get a sense of this shared collective image. The island itself is very wild and used for local tourism, at one stage it was used by the Soviets to build sea mines. The old derelict mine factories and train lines still cover the landscape, leaving traces of its history behind.

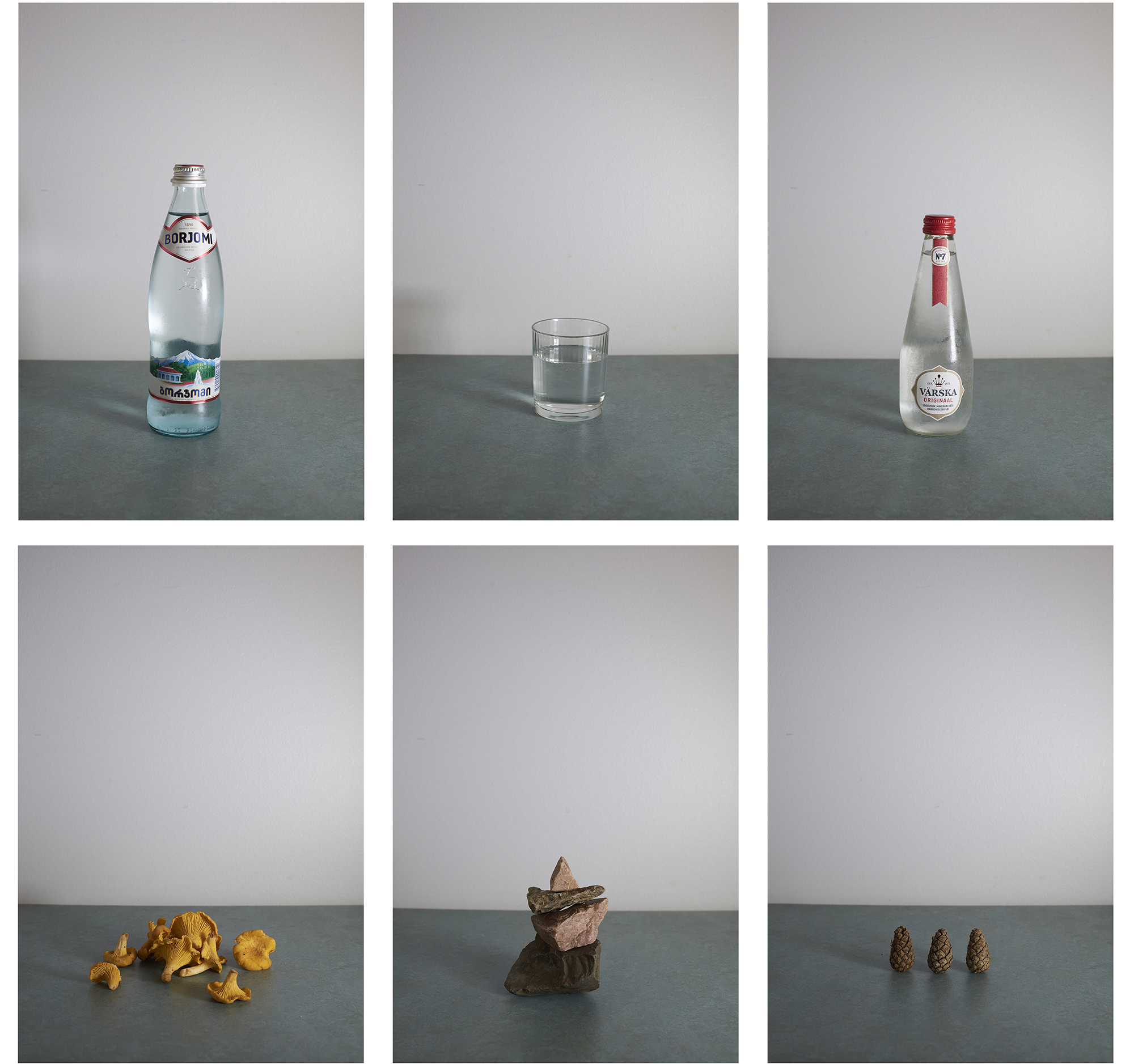

One image depicts, as if in an advertisement, two bottles of mineral water, a glass of water and various objects taken from nature. Do you feel that natural spaces are being commodified through phenomena such as ecotourism?

The grid acts as a symbolic archive, I produce these a lot in my work. The top row left to right shows a bottle of Georgian water, a glass of tap water and a bottle of Estonia water. These bottles represent the Soviet history in Tallinn and the tension of the past projected onto the different languages spoken in the city. The tap water acts as a symbol of Lake Ulemiste and provides nighty percent of the drinking water for Tallinn. Tightly protected it is hard to glimpse the waters of the lake, with the only open view seen from the airport. The bottom row of the grid is comprised of objects collected from the natural landscapes on my walks.

I think natural spaces are commodified by all forms tourism, period. With it tourism brings jobs for locals and financial gain for the economy, but is often destructive to the natural environment. Ecotourism should act as a fundamental premise for all forms of tourism. With the destructive effects of global warming becoming more apparent, we are losing what little natural spaces we have left. Ecotourism is a way to sustain and protect the natural spaces still left, whilst educating future generations and bringing benefit to local to economy.

Words: Megan Wallace

Editor: Emma Bourne

SaveSave

SaveSave