Artist: Jon Henry

Words: Emma Bourne

This story was previously published in Edition 03 of Jungle Magazine.

In 2008 three detectives were found ‘not guilty’ for all charges placed against them for the murder of 23 year-old Sean Bell, who died on the morning of his wedding day in a swarm of police bullets two years earlier in Queens, New York. The event led to silence across the city as civilians reflected on the extent to what had been lost – the loss of life to Bell, the loss to his fiancé, mother and children, and also the loss of an American citizen. At this time, photographer Jon Henry was also living in Queens and could not escape relating the event to his own life; “I will never forget the images from that night. That same year, my friend was getting married and I was at the bachelor party and that was all I could think of. What if this happened to him, to us?”

It was the death of Sean Bell that led Henry to begin to really question the position of African American men across society; he found himself asking why are these men constantly subject to bouts of violence and charges by police officers and why are their deaths captured and reported in such a senseless manner. Several years have now passed, and Henry’s reflections remains the same,

“The problem is still across America. The black man is viewed as a threat and that is perpetuated throughout the media. That is what makes these horrific stories more frustrating. When you hear, cops say, ‘they feared for their life’ in situations that don’t warrant a gun to be fired, it turns innocent men into victims.”

In wanting to both challenge and reflect upon the senseless deaths of young African American men, Henry began his photographic project Stranger Fruit. Within this project Henry primarily approached mothers: mothers in insolation and mothers with their sons. Mothers, who understand too well the risk that their own sons could be subject to violence or murder and become, caught up in crime due to the colour of their skin. Working with members of his own family, family of friends and families who approached him, Henry seeks to explore the role of the mother within the aftermath of violence;

“Mothers play an enormous role in every facet of their child’s life. Throughout the project I am thinking of those mothers who have lost their sons… Yes, these are African American mothers and a situation that primarily involves this community, but everyone has a mother. What does it mean when a mother cannot protect her children?”

For the mothers of sons subject to death by violence, the pain of the event resonates beyond the sadness and worry one may feel when reading a newspaper article or viewing press images. Every mother worries about their children, regardless of their age. Mothers spend years making decisions that impact the growth and development of their children. To have their child taken due to the choices that other people have made can leave a mother feeling powerless.

This sense of hopelessness can be seen across the images Henry has taken of mothers away from their children, stood or sat in contemplation. He asks “How do day-to-day activities change after these tragedies? How do these mothers handle solitude and what must be going through their minds?” In Untitled 2, Co-Op City, NY a mother sits alone in a dimly lit dining room at a table set for two. The mother sits side on to the camera, with her eyes downcast toward the empty chair to her left; she sits in solemn reflection. To the viewer it is not clear whether she is waiting for someone to join her at the table, or whether someone has just left. In many ways this echoes the reality many mothers tied up in African American politics face; the worry when their sons leave the house and the fear that they may not return.

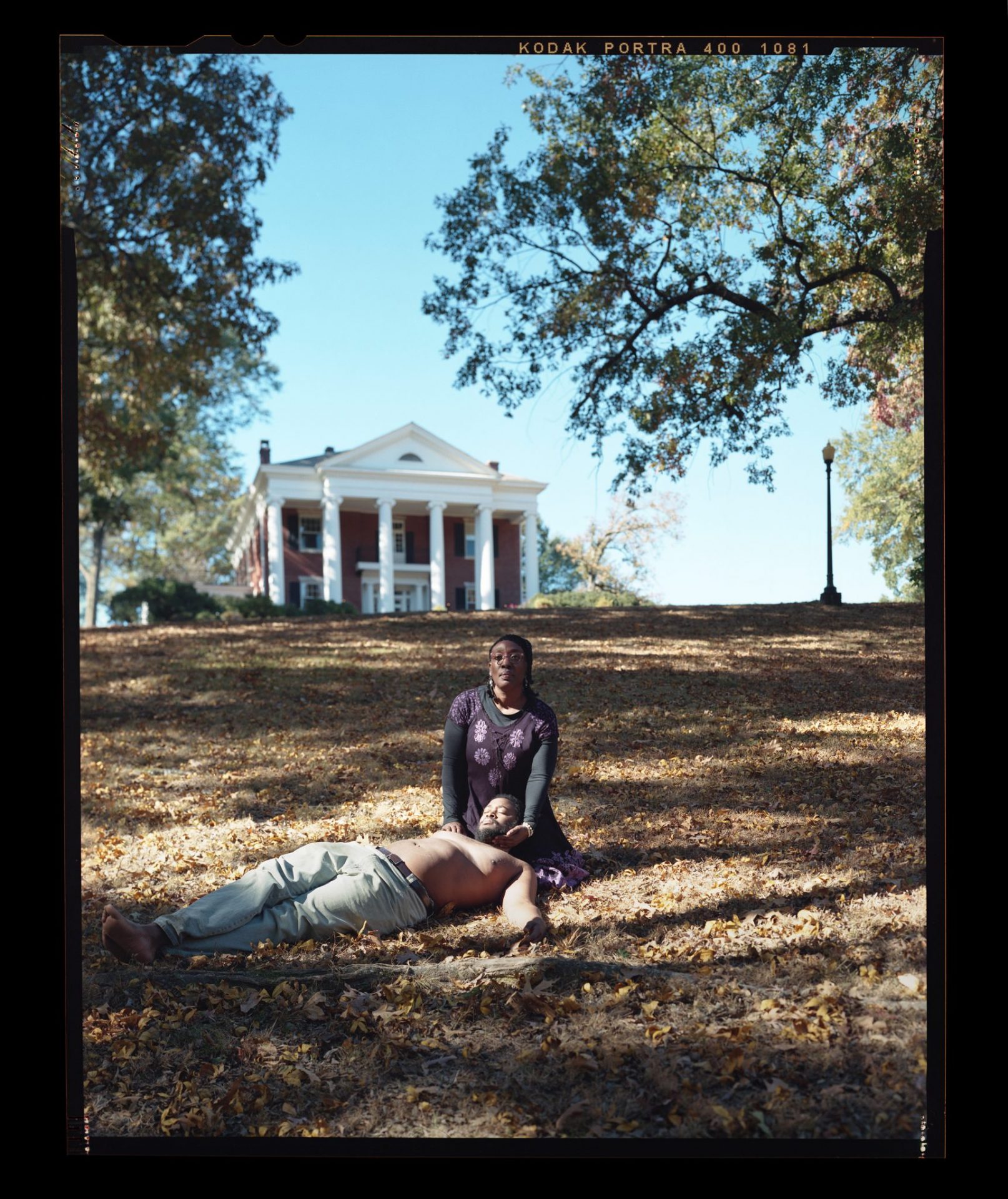

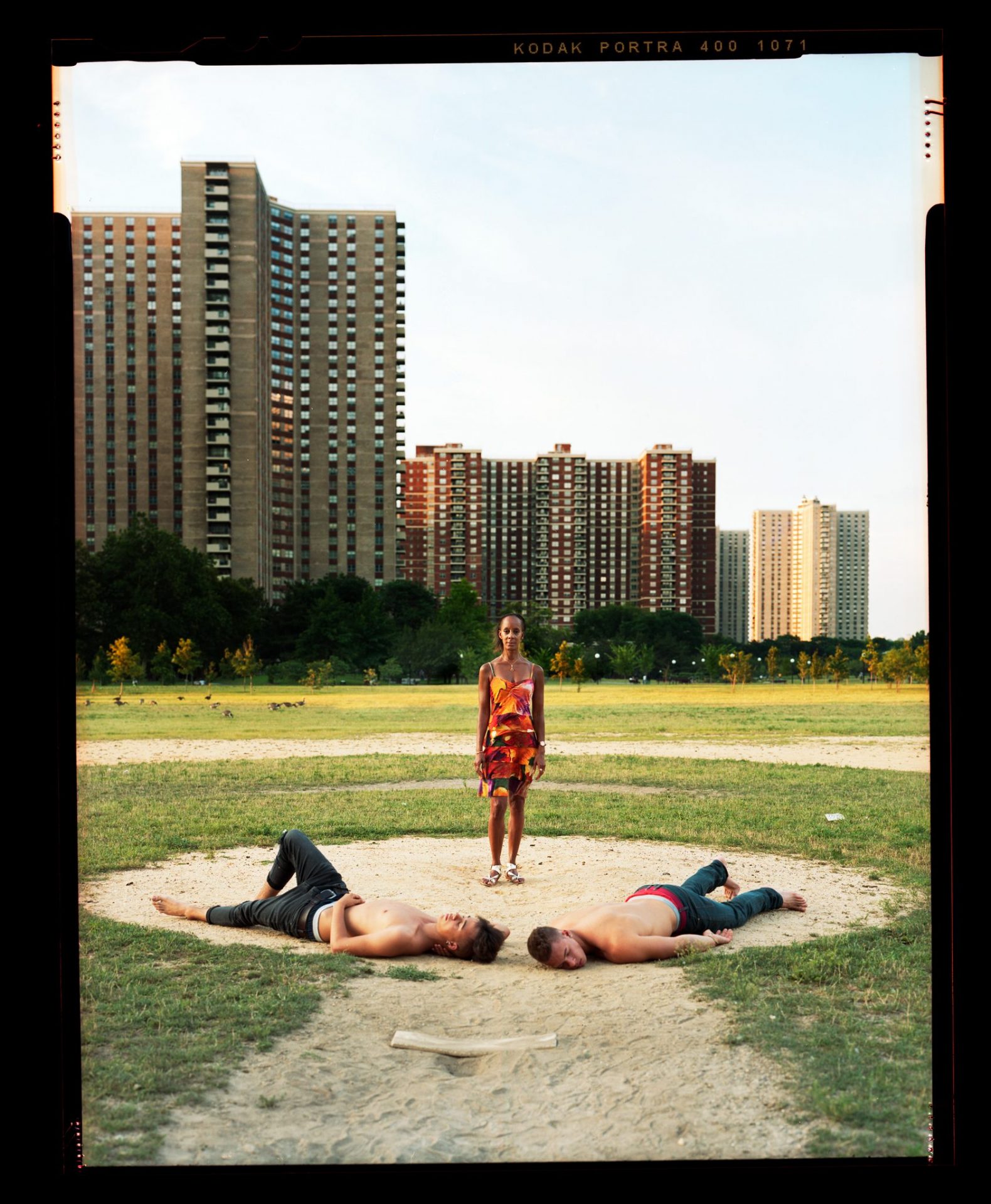

As well as photographing mothers, Henry has also photographed mothers with their sons. Here Henry asks the family to adopt the position the Virgin Mary takes on in Michelangelo’s 1499 sculpture, the Pietà, where she cradles the dead body of Jesus after his crucifixion. In place of the Virgin Mary is the mother, and in place of Jesus is the mother’s son, or sons. In the majority of Henry’s images, the son(s) do not look at the camera; they appear with limp bodies and downcast or closed eyes. The ages of the sons range from babies to teenagers to grown adult men. In Untitled 5, Parkchester, NY, we see a mother cradling her baby. The mother stands strong and her pose appears natural; one adopted by many mothers to care and protect their infants. In Untitled 19, Magnificent Mile, IL the mother takes on a similar pose, but with her teenage son. The son appears to be almost the same height and size as his mother; his body poetically positioned across his mothers lap. Sat in a busy city centre, this pose takes on a less natural appearance; in the context of Henry’s project we somewhat question the son’s need for motherly protection. Though, whilst it is the sons who become the victims of violence, within Henry’s work it is the presence of the mothers that hold our focus. As with the reality of violence against African American men, it is also the mothers who in many ways seek the protection. The mothers who seek to keep their children safe and the mothers who are left to deal with the tragic aftermaths.

It is also the mothers who we see first in these images; her confident stance, her determined bold gaze; she appears fearless. The stance of the bold mother in public spaces with her son(s) is very different to the solemn and withdrawn gaze of the mother captured alone in her home. The mother faces the world with a resilience which Henry reflects, “is essential to the project. The mothers know the reality, that their sons can become victims in the blink of an eye, so they have to be strong, for their own sanity, and strong for their family.”

Untitled 27, Providence, RI depicts a mother kneeling in the middle of a quiet road near her home, with her two young sons in Rhode Island. One son, taking on the position of the dead Jesus Christ lies limp in his mother’s arms; raised off the floor and stretched out, we see the young boy’s ribs push against the surface of his skin, as Jesus’ do in the Pietà sculpture. The other son gently rests his head against his mother’s right knee as if asleep or resting. Perhaps he is also suffering or perhaps he has just escaped the violence this time. Ironically the mother in this image is dressed in white and blue, reminiscent of the colours the Virgin Mary is often depicted wearing. With a tint of pink lipstick, a neat halo of Afro and the sun against her face, this image places the mother in an almost saintly light.

Sat in the middle of the road, there is something quite peaceful about the subjects in this family; the mothers calm composure and the young boy resting in the sun. Though, whilst the middle of a road isn’t a place that families would typically sit, it is a place that has too commonly seen the gathering of mothers around their injured or dead sons. The mothers who look upon others’ sons and the mothers who realise their son(s) have been hurt and rush to be with them. Location is carefully considered across all of Henry’s images; each shoot takes place in areas that are close to the families’ homes.

“I scout each location prior to meeting with the family. There are different markers I’m looking for, that tells the story of the location. The choice of locations is also a loose reflection of where violent murders have occurred… a park, in the middle of the street, near the home.”

Sat in the middle of the road, there is something quite peaceful about the subjects in this family; the mothers calm composure and the young boy resting in the sun. Though, whilst the middle of a road isn’t a place that families would typically sit, it is a place that has too commonly seen the gathering of mothers around their injured or dead sons. The mothers who look upon others sons and the mothers who realise their son(s) have been hurt and rush to be with them. Location is carefully considered across all of Henry’s images; each shoot takes place in areas that are close to the families’ homes.

“I scout each location prior to meeting with the family. There are different markers I’m looking for, that tells the story of the location. The choice of locations is also a loose reflection of where violent murders have occurred… a park, in the middle of the street, near the home.”

When shooting, Henry uses a large format camera on a tripod; a lengthy process that involves placing a single sheet of film into the camera, manually setting the focus, determining the aperture and shutter speed and then waiting until the image is developed to see the final result. When discussing his use of large format photography Henry draws upon the importance of time,

“I prefer to take my time with each subject. I feel that it helps calm everything and everyone down (myself included). The smaller details matter more. This process also allows me to find a balance between being meticulous and letting things happen naturally. For the subjects, it allows them time to reflect on the situation at hand and let their emotions carry them through the process.”

Taking the time to stop and reflect on the world around us is never more important than in times of violence and trauma. Reflection is essential for change to occur. As Henry discusses,

“The goal isn’t for the work to be seen in a gallery and then forgotten, but to encourage a dialog. There is a problem in our society. Police brutality and the African American community have a storied history. These men did not deserve to die. When can we acknowledge that there is a problem? Once we acknowledge it, we can actively work on solving it.”