Interview: Veronica Gisondi

Artist: Kentaro Okawara

Interpreter: Hinako Matsumoto

Art teaches us that meaning can be hidden in every ordinary sight, gesture, and motion. It also shows us how things that are shared but barely disclosed, or rather, profoundly human “things” – instincts, cravings, fears, obsessions – can, with different motives and outcomes, find a way out in the work of the artist.

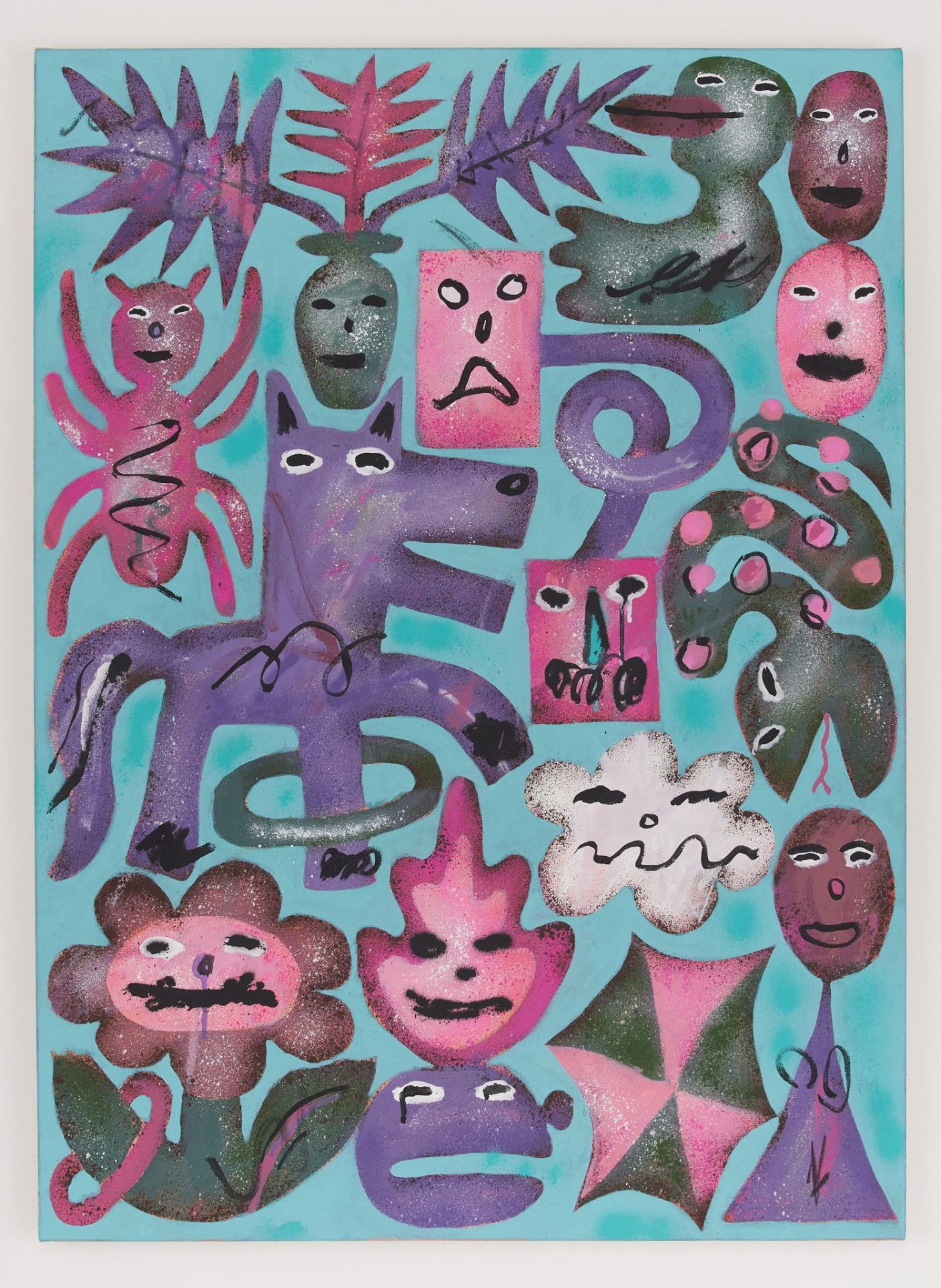

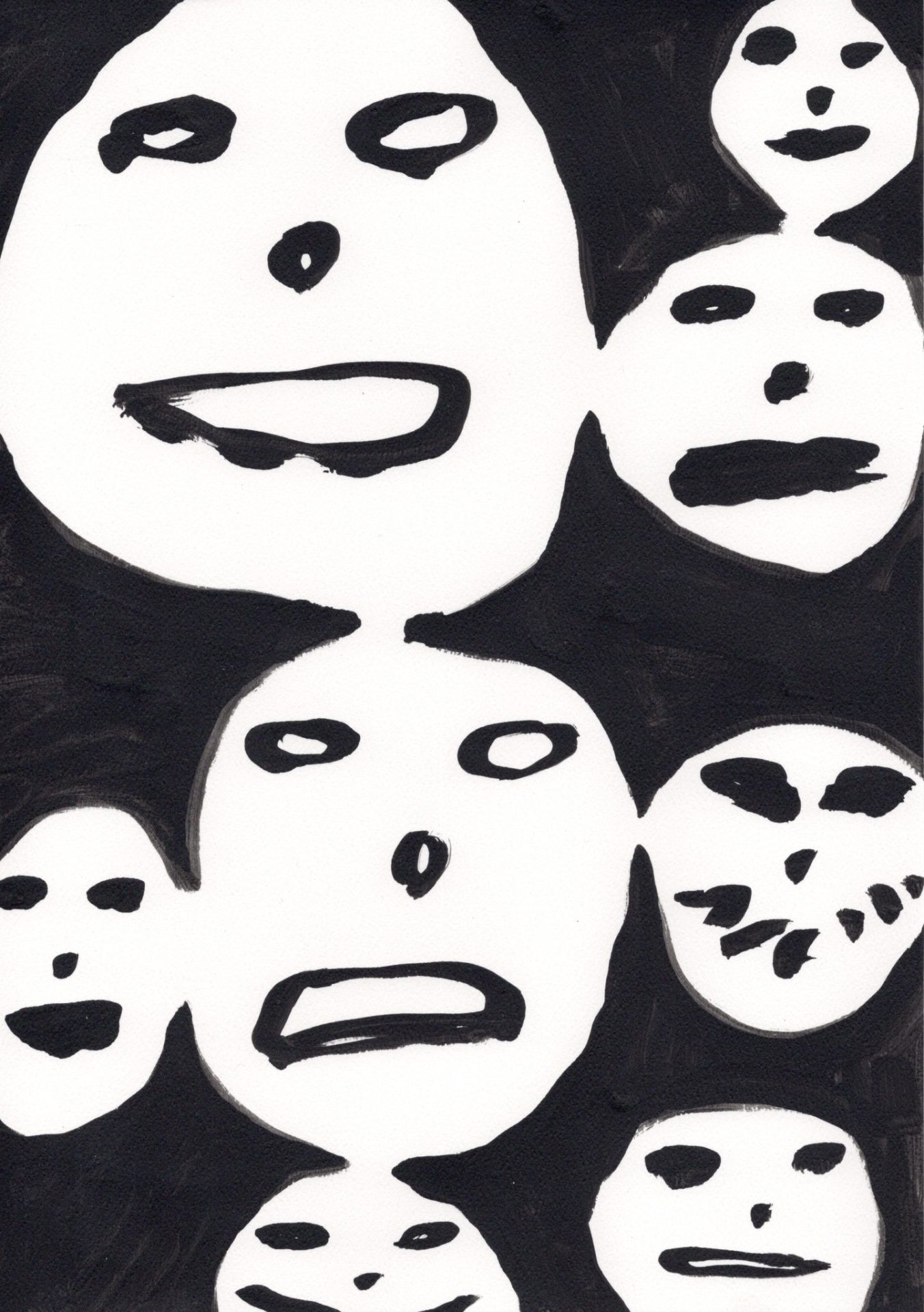

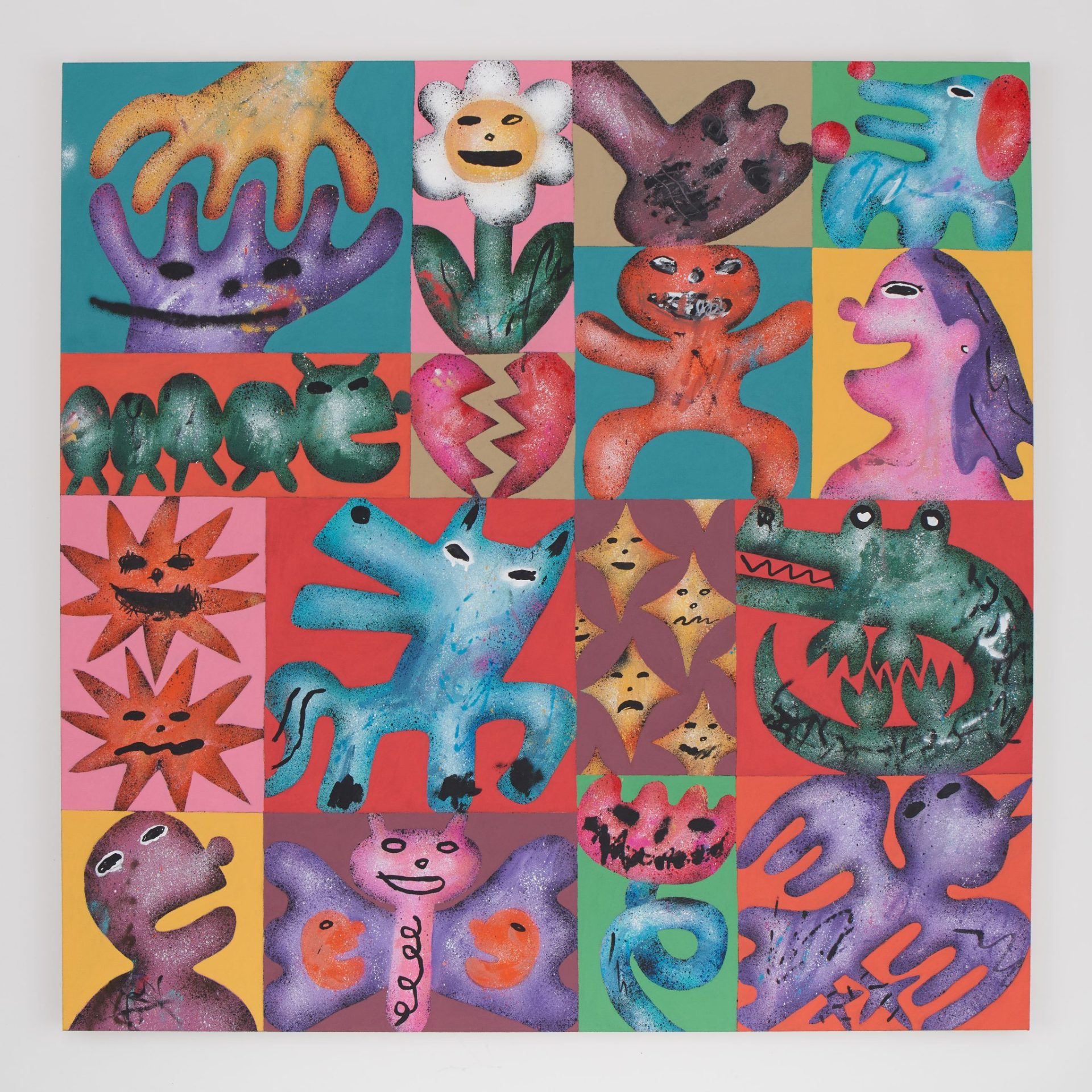

Through a bright, uncurbed sensibility, a confidently emotional attitude, and a fascination for even the smallest of everyday feelings, Kentaro Okawara does just that. His art plunges headlong in the uncharted territory of non-verbal communication, embracing the lack of answers intrinsic to any generative process with curiosity and candour.

We spoke about the postcard exchange that forebode his artistic career, welcoming and treasuring the unexpected, the MORE LOVE universe, his recent collaboration with BIMBA Y LOLA, and understanding process both as a document of one’s practice and a testimony of its transience.

Kentaro Okawara’s upcoming exhibition with Hato Press, Our Life, opens on 28th July in Goswell Rd., London EC1M 7AA.

The kind of simplicity, immediacy, and self-sufficiency that characterizes your work echoes that of children’s drawings. When and how did you realise this mode of expression would be central to your practice?

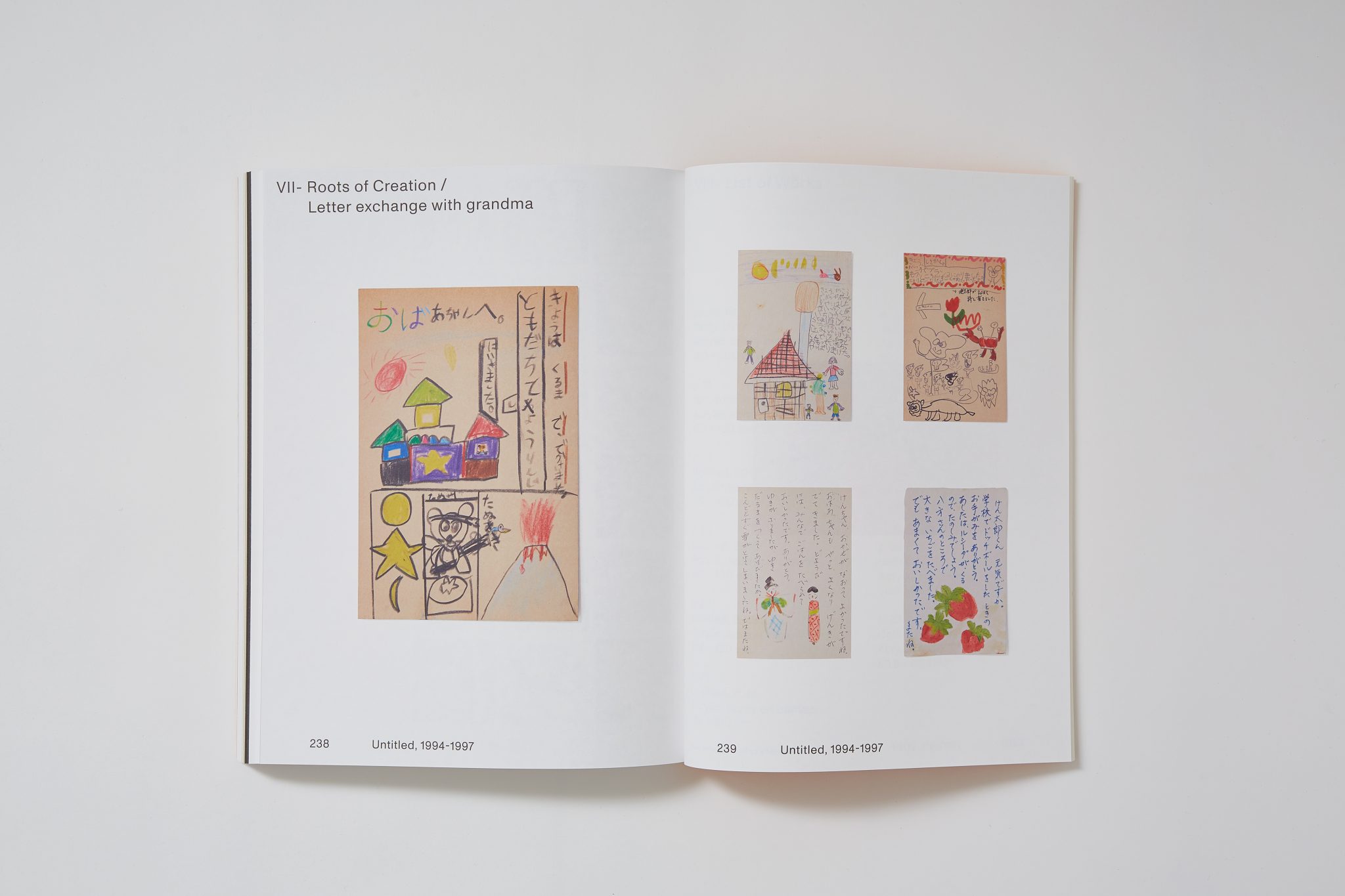

When I first realised that I wanted to create something, to draw something, it was when I started to exchange postcards with my grandmother. It lasted for about three to four years, and when I entered high school, it was over. I kind of forgot about it. But then, when I got into university, I knew I didn’t want to become a salary man and I didn’t want to study anymore, so I chose arts. Then I actually thought about what I wanted to do, or should have done, and realised the roots of my creation and motivation lie in my childhood – in the memory of playing with my grandmother. Having someone I could interact artistically with was not an ordinary experience. It was special.

What is it that captures you about everyday gestures and emotions, and how did you originally find out you were fascinated by them?

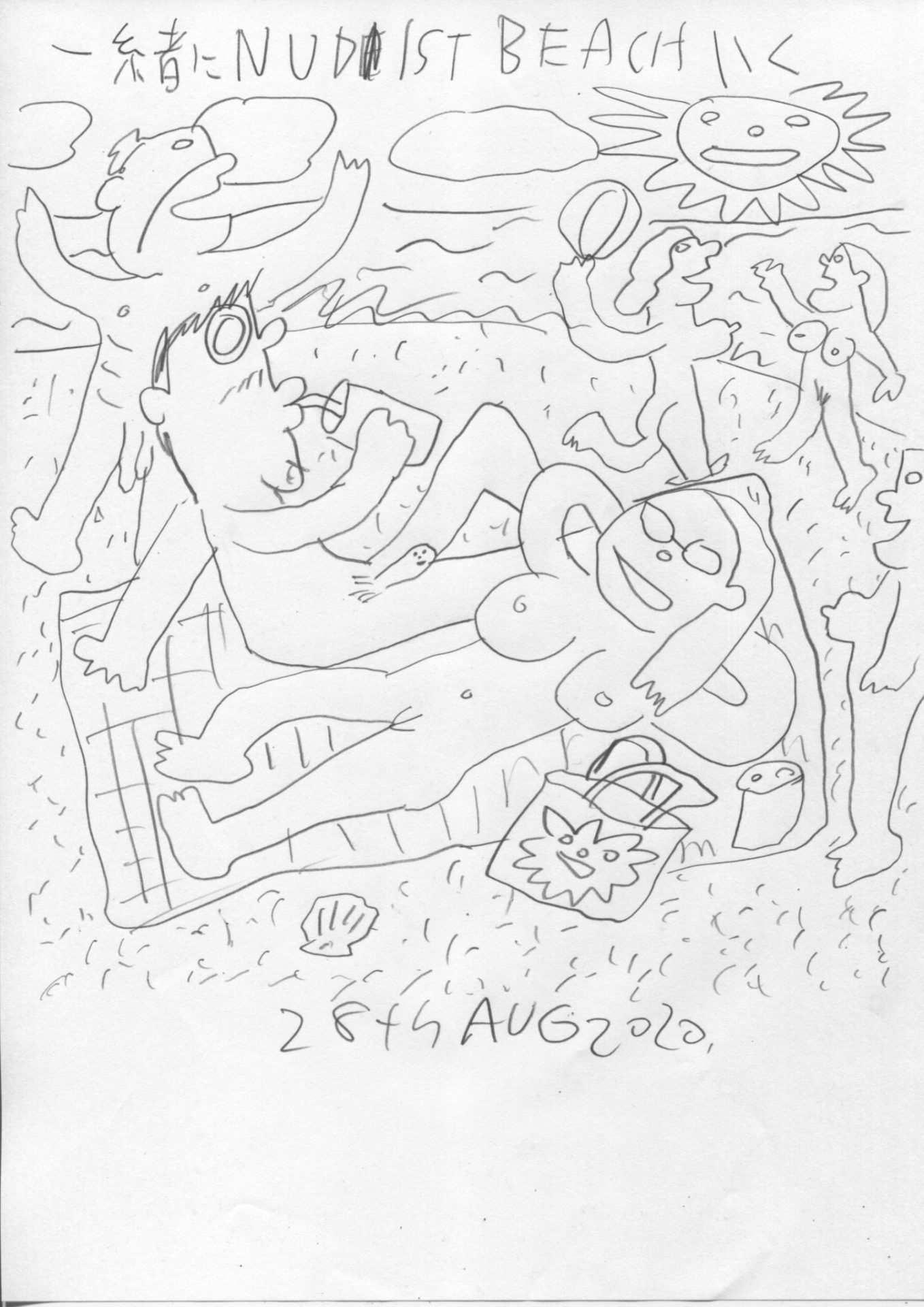

It’s difficult to translate into words, I guess, because it’s all about feelings. The relationship with people, those dearest to you – your girlfriend, your friends, family – that is everything for me. I don’t know where the idea came from, but it’s very important to me. That’s what I really cherish. It could be anything – any small thing in people’s everyday lives or emotions. Trivial things, like people walking their dog, or looking at their dog in a lovely way, a girl dropping something on the floor, then crying, and me feeling sorry for her but feeling happy when she’s smiling… none of that is a given. Each ordinary scene is such a special moment. For example, when you watch a film with a heartwarming story, you feel like: ahh… or when you’re surprised, you’re like: AH! That sort of emotional power, or movement, translates to my painting. To me, it’s important to think about these tiny things – to regard and appreciate them as moments that enrich one’s life. I paint to crystallize those moments, and to give people an opportunity to think about it.

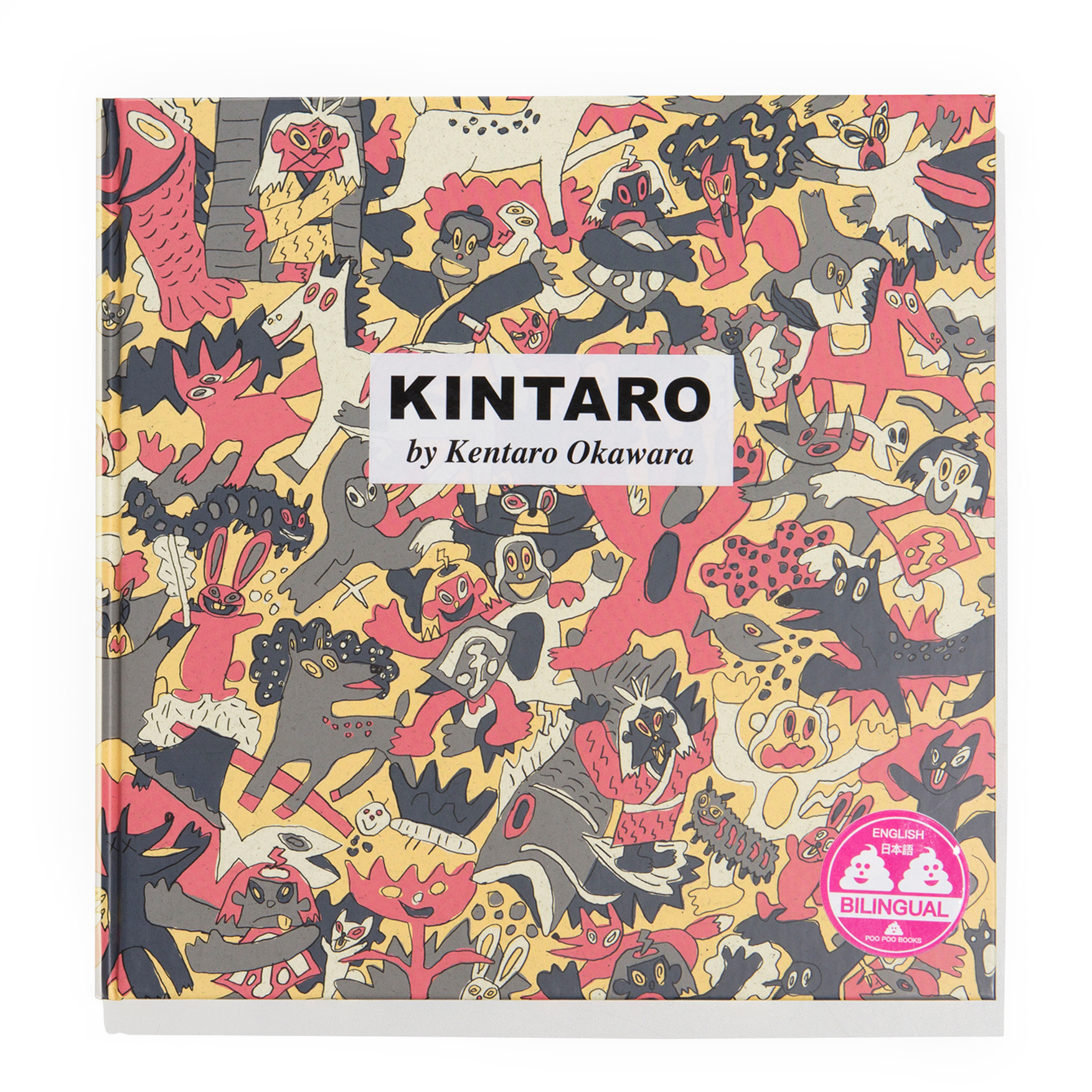

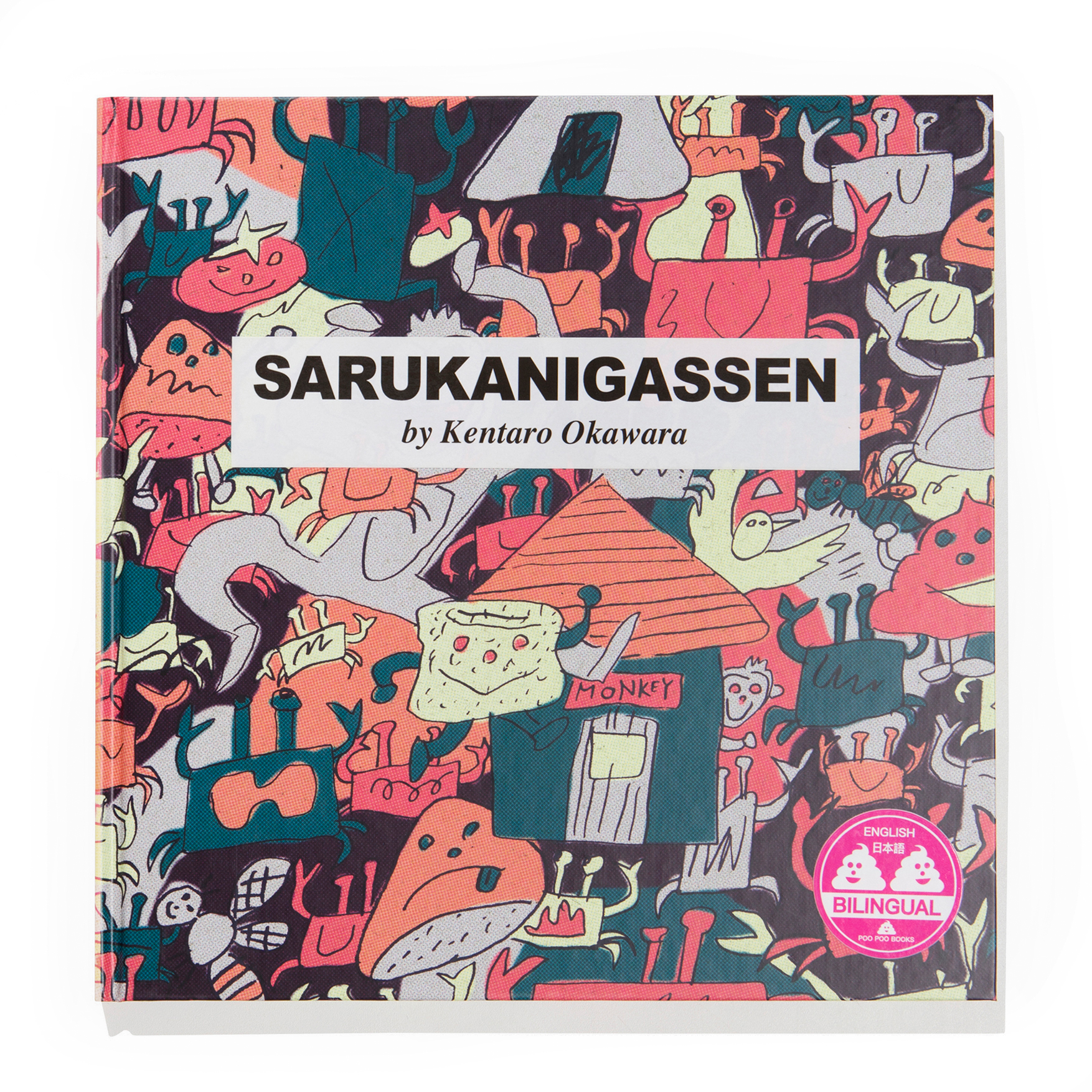

You’ve designed several bilingual picture books. How did they come about? Could you expand upon your relationship to Japanese folklore, folktales, and the way you connect with (non-)traditional forms of storytelling?

When I was small, I often went to the library with my mom, and she read books for me. Just remembering that I had this experience with my mom, that she was reading to me, is already special, and I think it was from this I gained a kind of richness in terms of emotional expression. In 2016, with a friend I often hang out with, I started the picture book project. This friend, who has a child, once said: “I actually don’t have any books I want to read with my kid.” He wanted to create one that could be appealing. The format of Japanese folktales is really… different. It feels a bit old. The story doesn’t need to be changed, but it can be delivered in a more modern way – a way kids can be fascinated by. That’s how the work started.

About the relationship with Japanese folklore, it’s not that I have something particular about it. In bookstores, folktales are usually in a different corner than other books. The designs always stay the same in a kind of old-fashioned way. People might be starting to care less about them. Although it’s not necessary, I want to make something that entertains kids who live in this era. For the books, we choose stories that reflect our experience and suit my current art mood or style – and the playfulness in it – and try to create something that can make kids happy. I also like the book format because of the physical experience of turning the pages, so I think that aspect should stay. I want it to stay.

You’ve previously spoken about exchanging postcards with your grandmother. What did you like about it at the time? What have you learned from her, her art, and the way the exchange unfolded?

It happened quite a long time ago, so I don’t remember everything too clearly. The reason why I started, as you probably know (perhaps you’ve read it in some other interview) was that, when my grandad died, my grandma had to live alone. She lived about three train stops away from my place – a bit far for a kid to travel, so I said I would draw her postcards. I would draw subjects I found interesting at that moment or that I was passionate about, and then my mother would tape the drawing to a postcard and send it to my grandmother. What I was happily surprised about was that she also responded in a picture format. Sometimes she would try to draw Mickey Mouse, or Hello Kitty. Thinking about her age, how elderly people try to communicate in a way that’s at the same level of a child’s, is a kind of special, unique experience in itself. I was looking forward to receiving her postcards every time.

Some of the features of the postcard format recur throughout your work, not just in terms of ratio, but also considering their narrative autonomy and self-contained composition. How would you describe your image-making process?

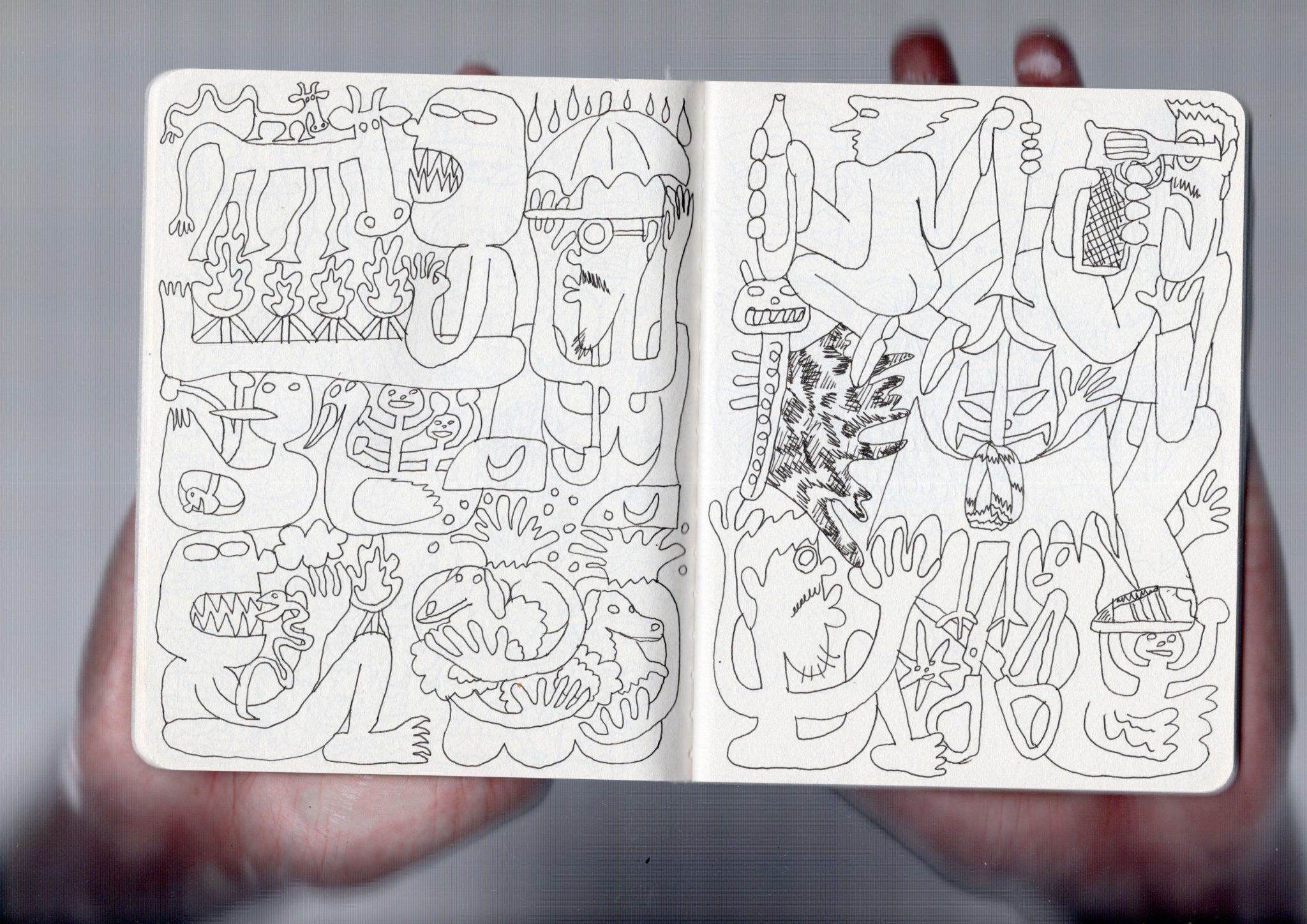

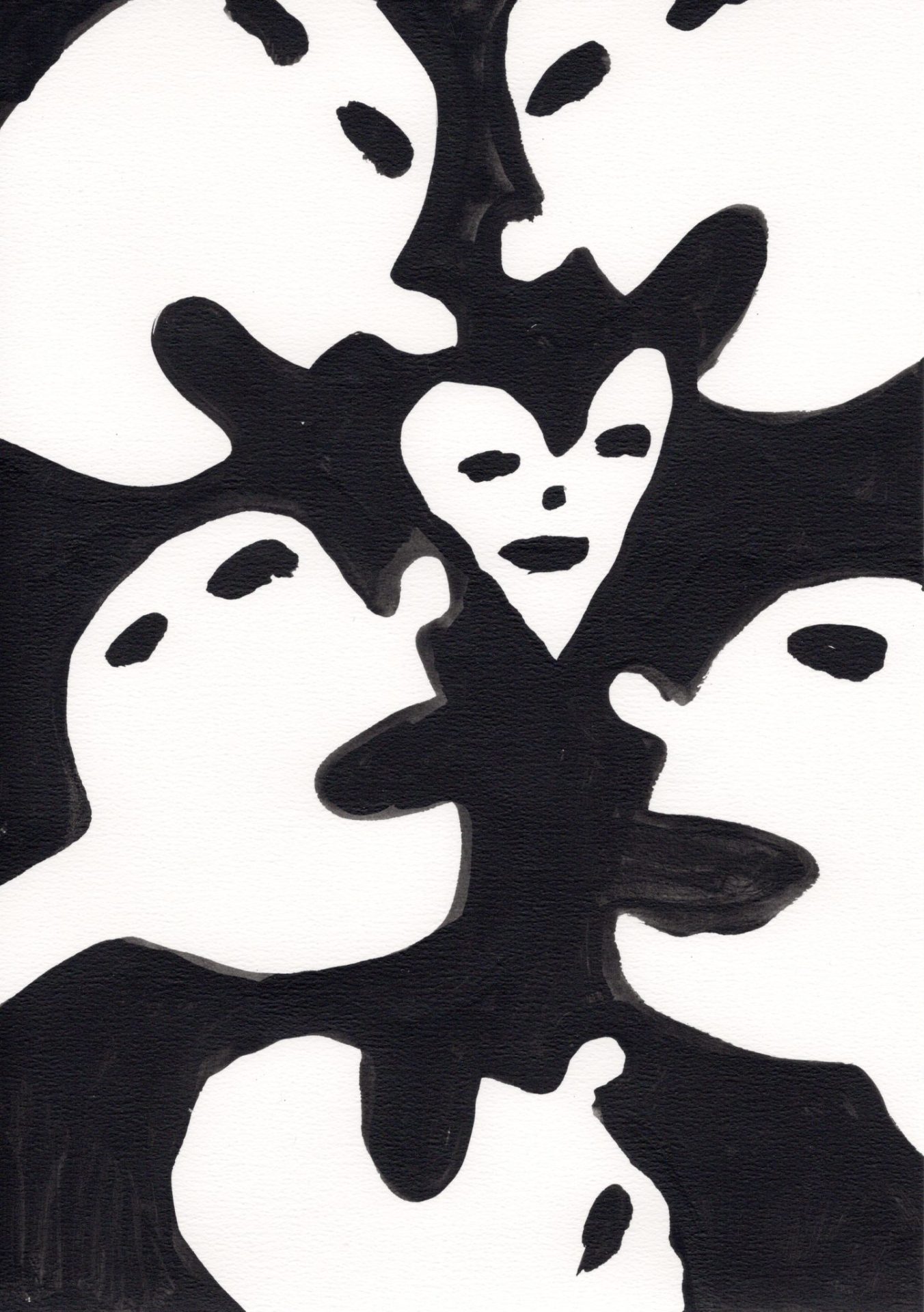

There isn’t a consistent rule over my entire work, as it’s about my feeling. However, I think I do have some sort of “rules” that change over time. But there’s always going to be a time when I want to break out of a particular style, to get away from it: for instance, right now I think I work too much on very detailed work – that means Wild Kentaro is about to come out!

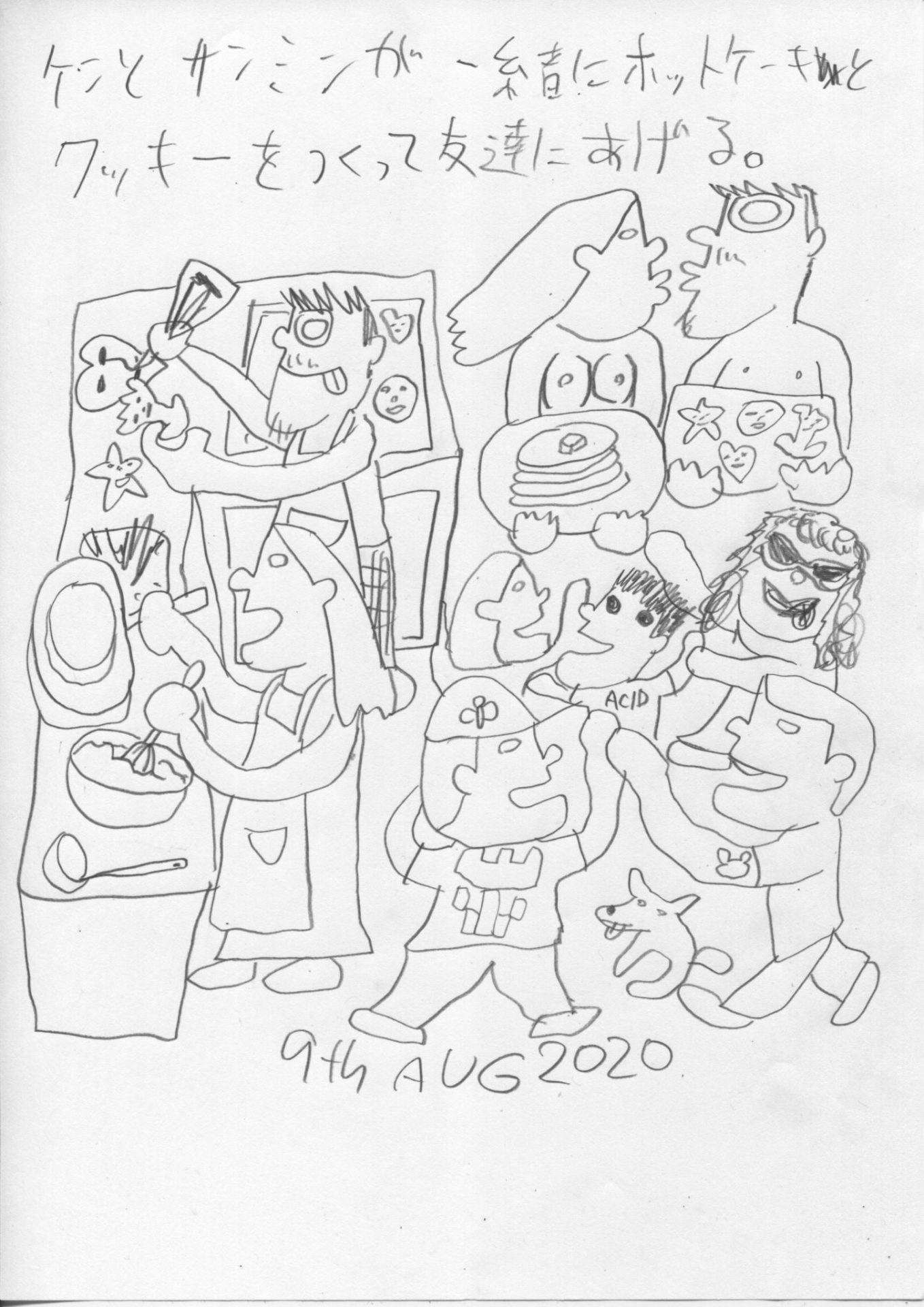

Motifs are something that naturally comes up in my mind. Process-wise, when I work on postcards, I don’t think I really care too much about balance or composition. Or maybe I could be unconsciously thinking about it. Of course, when I do paintings, I care about that and colour combinations, but it’s a transient feeling related to the moment when I’m making an art piece. If I look back at my works, I can still feel how, at a definite time, I had a specific toy car on my mind, or I was in a certain stage in life… It’s a kind of history of my feelings, emotions and thoughts.

What do you enjoy the most about your practice?

Well, of course I love showing my pieces to everyone!… When I’m painting I struggle a lot, but I enjoy it as well. Sometimes it’s painful because there’s no clear answer to what you’re feeling, to how it comes out from you. I always have to visualize it for other people, and there’s no clear answer for that either. Sometimes it might come out differently from how I really felt. It’s always kind of difficult, although even then I do enjoy it.

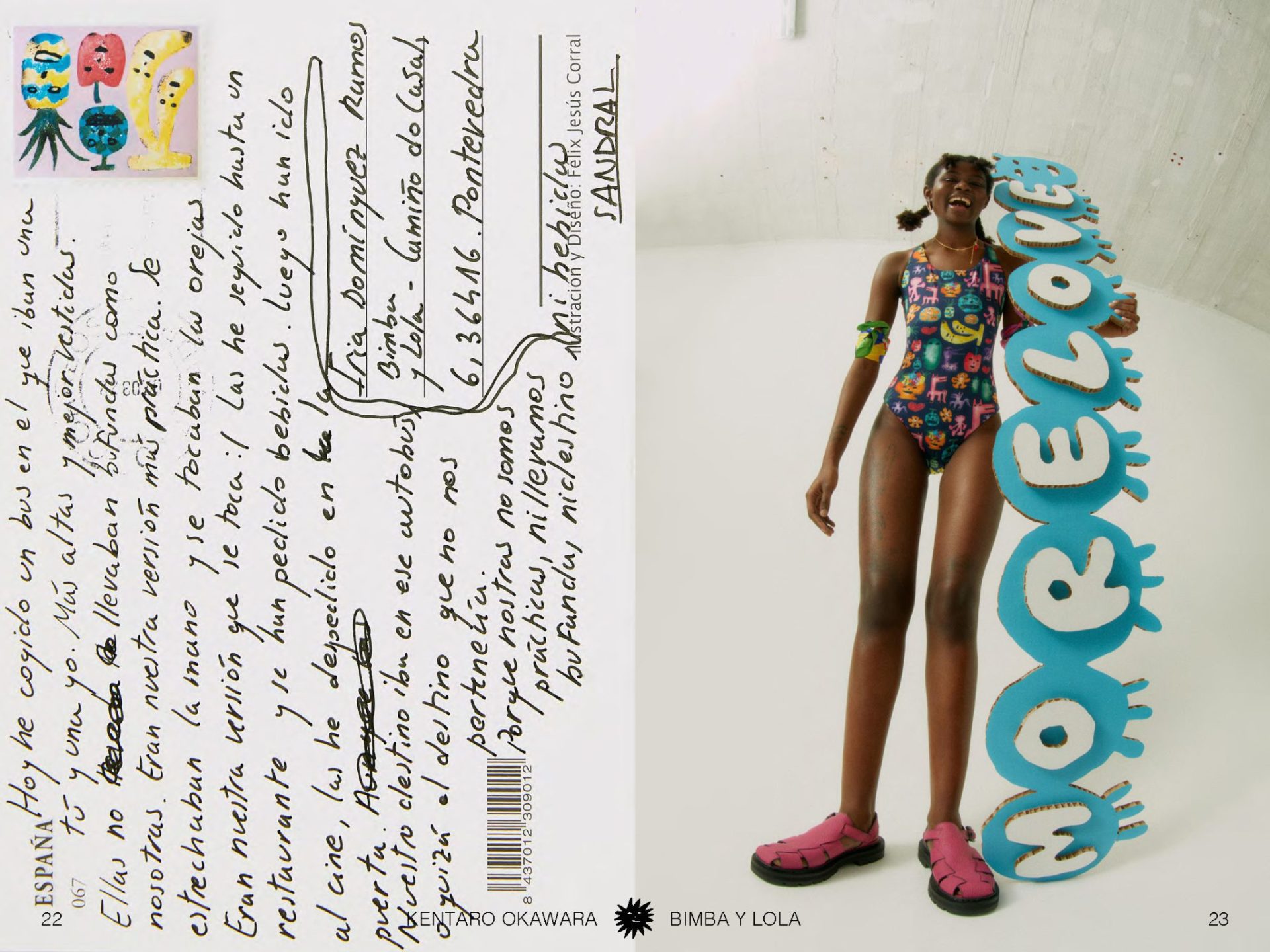

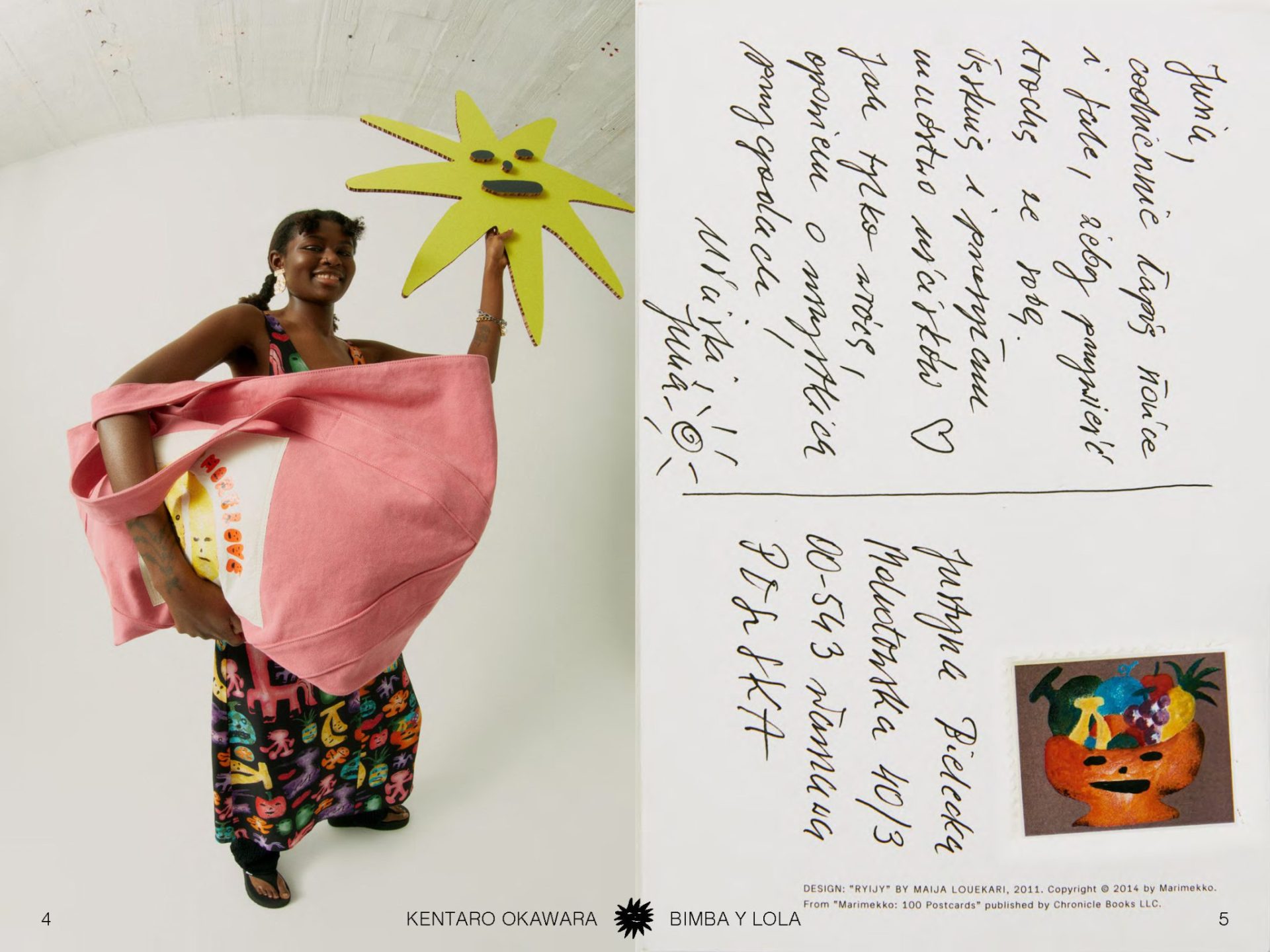

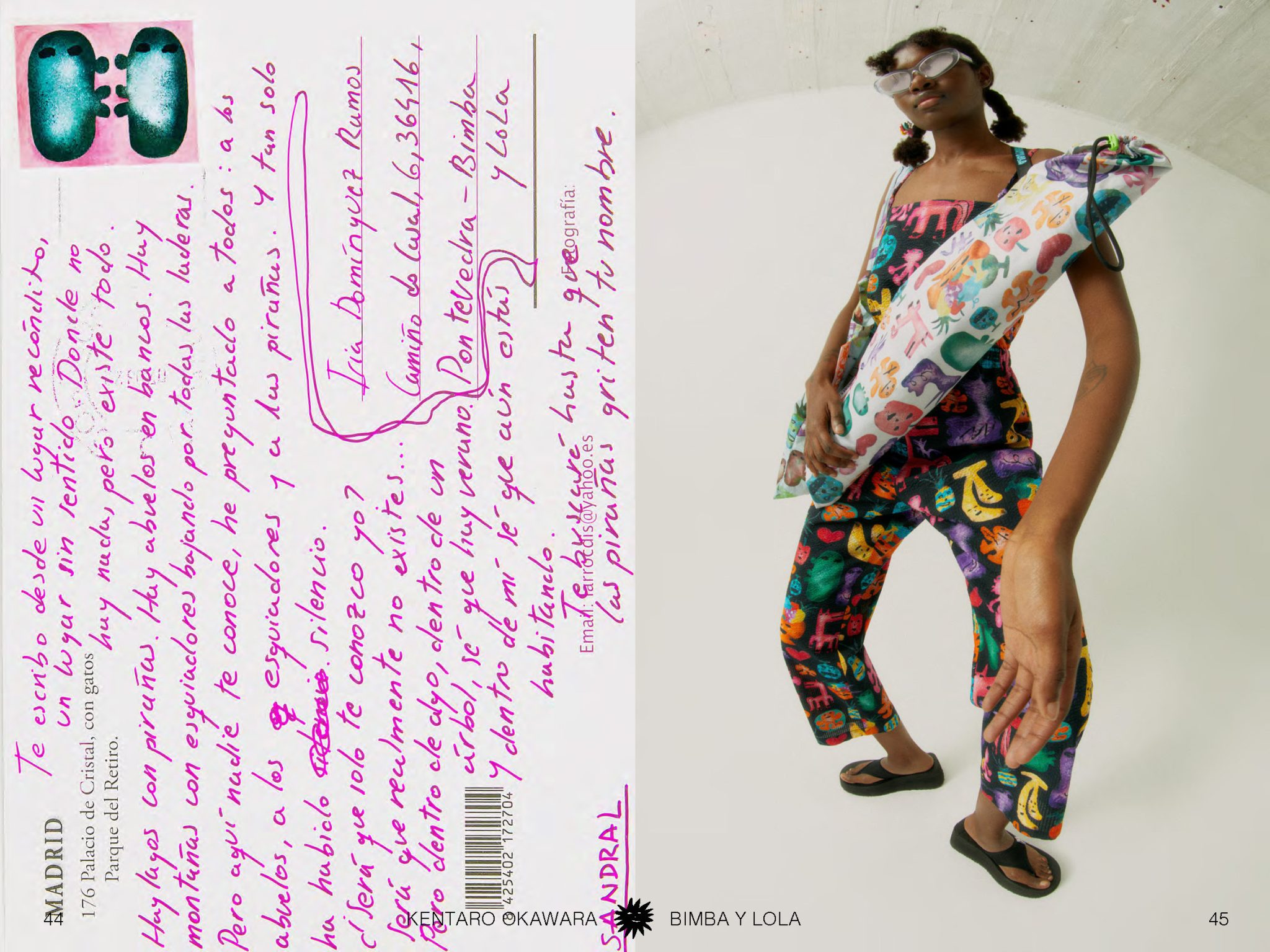

I recently learned about your collaboration with BIMBA Y LOLA and the MORE LOVE campaign. Could you speak about how it came to be, what the collaborative process was like, and the way the concept was shaped? How does this work intersect with, enrich and expand the MORE LOVE universe?

The collaboration started before COVID-19 happened, and when the pandemic hit, the project had to halt. At the beginning, we were discussing logo designs and things like that, but after Corona we changed concept and they changed their mind: they wanted to do a bigger collaboration, an entire collection with my designs.

MORE LOVE is a project I started three years ago. It’s a brand, but it’s also a kind of slogan. We mostly do printed graphics on simple t-shirts, which is different from making an artwork that you have to go and see in a gallery. A t-shirt is closer to people’s lives. I want MORE LOVE to be something more meaningful than just merchandise of my artwork.

BIMBA Y LOLA liked the concept behind MORE LOVE, which also resonated with their collection. Being involved in such a big campaign has been quite an experience for me, and thinking about the details of women’s apparel was also a discovery, as we never did that before.

You have developed your own vocabulary throughout your work. How do you relate, within and outside your work, to spoken and written language?

I’m glad you noticed that. To me – in my life, my art, and everything about me – communication is what matters most. Language is just one of the methods to communicate, and so is art. I started to focus on thinking about communication, and the richness that can be communicated through art, when I had my first international show in Portland, US. As I mentioned earlier, I didn’t study too much, and I wasn’t able to communicate in English at that time, but people came to me. They hugged me, congratulated me… I was so fascinated by and excited about seeing people react in front of me. I also loved seeing other people’s work in the gallery, being moved by an art piece made by someone whose life I don’t know anything about. Communicating with someone who you don’t really know, through art – this is crazy. It transcends generations, cultures, languages. That really matters to me, and moves me. That’s why I feel honored by hearing you say my work has its own vocabulary: we never met before, and I don’t think I ever mentioned how I feel about communication, but still, my work delivered some sort of language to you. I really appreciate that. I guess it’s good that I kept drawing [laughs].

Within your production, certain figures and elements are recurring too, almost as if they were archetypes, giving life to a personal iconography. Is this aspect linked to the pursuit and development of your own voice?

It’s kind of related to things I mentioned before. When I was young, four or five years after graduating, my aim was to create drawings that had never been seen or created before, and that would surprise people. I wanted to feel excited about that. It was about making other people feel something through my art. And then I realised I was disposing my art’s possibilities of communication, and how it was a bit of a shame. That’s when I started to draw in a simpler way – a way which could communicate to everybody. I also feel that, naturally, I’ve become more open-minded. That’s what made me paint simpler motifs: to achieve a mutual balance between my ideas and coming up with motifs that could convey those to everyone.

How do music, rhythm, beats, patterns and soundscapes play a role in your work? What have you recently been listening to?

Music is very important for my work. It can change my mood, make me remember… I tried singing, dancing, playing piano in the past, but they weren’t really for me. Now I mainly listen to RnB and hip hop, while I find it difficult to resonate with rock or punk music – that kind of loud guitars, or very expressive guitar sounds. It’s a bit difficult to digest. I also think it’s good to listen to local music when I have a show somewhere. During my show in Mexico, for example, I would listen to Latin music as a way to channel my mood to that of the area.

How do you juggle between media and outputs as diverse as print-making, sculpting, designing clothing items, as well as art and children’s books? Do they respond to different needs?

Whatever media I choose, be it sculpture, graphics, or picture books, the fundamental base lies in painting. The way I choose outputs is similar to how I would pick a material or style. Frankly, I’m choosing according to my feelings. I quite enjoy working in creative direction too: thinking about a show’s concept, ideas, and planning, while treating and designing it as a whole presentation – a space for people to experience my work.

How do you deal with expectations about the finished work – be it an image or an object?

I don’t really think about how people might react. It’s difficult for me to create artworks thinking about people I’ve never met, so I don’t do that. I’d rather stay true to myself and care about those who are dear to me. That’s the only way I could live as myself, although I do hope that, through my painting, I can generate a communication with people I’ve never met or spoken to. That’s what allows me to do what I want to do, and how I create things.

What about your own expectations?

Well, basically, I struggle with that everyday! And I think it’s true not only for me, but for everyone, you know? Life is hectic, but you can’t just run away – you have to deal with it. Sometimes you can swing by and enjoy it, even if you’re in a difficult situation that could put your confidence at risk. Yet we have to strive for it: we have to live our lives. I try not to turn my back to it, and just strive for what I do and what I am.

You’ve already mentioned this: how do you keep true to yourself?

I think you have to consider how much you intervene in someone else’s life and how much you communicate with others. The important thing is that you don’t pull off, or push it away, or shut others out. When you don’t know how much you can intervene in a person’s life, sometimes you’ll have to leave. That’s also a way of caring, of being considerate. It all comes back to what I mentioned at the beginning of the interview. Seeing people walking their dogs or your friends smiling – and the feeling of gratitude that ensues – won’t make any kind of drastic change, but it’s still important. Having that kind of attitude is key to staying true to myself.

Special thanks to Hinako Matsumoto for being our interpreter during the interview.